The disciplines of architecture and town planning are intrinsically interrelated yet in practice are often considered separately from one another. My understanding is that there are intersections between these disciplines but rarely do the systems behind these professions collaborate through sharing knowledge and project outcomes in meaningful ways.

Western practices are predominantly siloed environments, with linear and rigid processes causing the two disciplines to move in and out of a project by considering its outcomes in narrow-sighted ways. In contrast, my lived experiences of thinking from a First Nations perspective is holistic and multifaceted. All parts are interrelated and one must consider design thinking with spatial locations, relationships with place and reciprocity in actions to start with Country.

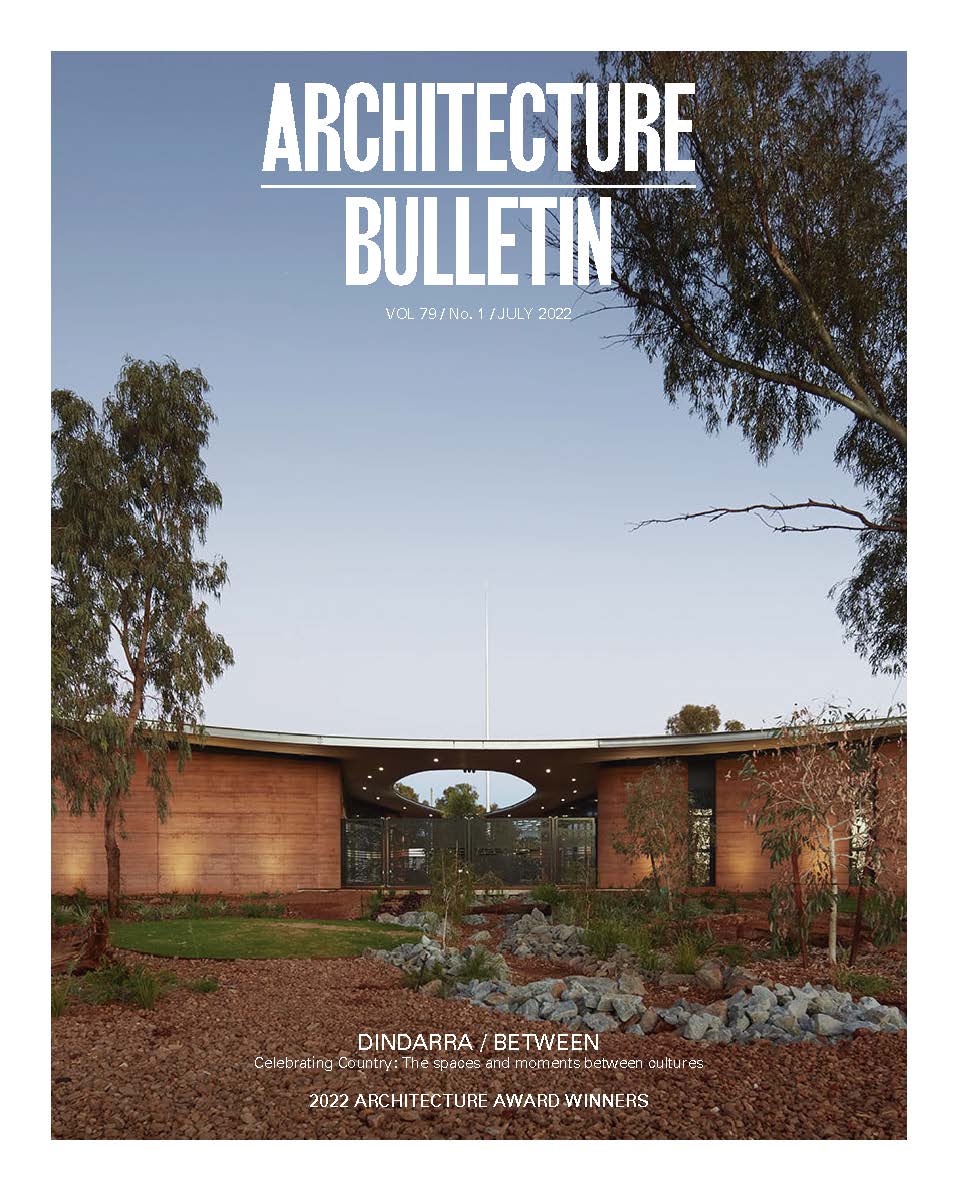

Gawura Aboriginal Learning Centre (2007, NSW Government Architect’s Office – Project Architect: Dillon Kombumerri) located at the Northern Beaches TAFE in Sydney provides a strong case study that starts with Country. The project provides actions of reciprocity through careful spatial location considerations and relationships with place and community.

These were achieved through sustained collaborative practices with the local First Nations communities who led the process of planning and design from the outset. The project was born out of community desire to create a space for Aboriginal learning within the TAFE site. Their involvement in the process was deeply embedded in all phases of the project and developed as a trusting partnership rather than a transactional engagement activity.

Susan Moylan-Coombs, a Woolwonga and Gurindji woman from the Northern Territory, who has lived on Gai-mariagal Country for over 50 years and former employee at the Northern Beaches TAFE commented “the campus site was unique because of a pocket of bushland in the middle. The idea was to create something that spoke about culture, spoke about purpose of place, which is education and then something that was welcoming.”

The siting of Garuwa in a central location within the TAFE campus was a powerful act of reconciliation and healing Country – creating a place where the whole community could come together while also providing a cultural facility for the local Aboriginal community. The project created a strong First Nations presence to enact Country as the centrepiece of the design thinking and approach.

Community leadership was integral to success to query and inform the parameters of planning the location of the facility and empowering a voice for Country. Community and culture were key drivers for the project for the architectural design and spatial location to build on and provide the built form manifestation of community aspirations.

Once the community had articulated their needs for the project Yugembir architect Dillon Kombumerri was engaged to facilitate the design process and work closely with the community in achieving their aspirations. He noted the importance of having an open mind when working with community through the practice of deep listening and the value of black-on-black enterprise to achieve mutually beneficial outcomes.

The design and planning process was led by community and Dillon highlighted the value of working at the pace of community without trying to force or rush outcomes. This ensured trust and reciprocity from both parties to collaborate with shared values and understandings of how the planning and architecture connected with Country.

As we learn to embrace, celebrate and commit to concepts and meanings of Country and community, industry and government need to reevaluate notions of reciprocity and collaboration between design and planning disciplines. The pressure placed on First Nations Traditional Custodians and Knowledge Holders to maintain holistic influence is mounting in light of the disjointed nature of planning and architectural disciplines. This is compounded by a growing sense of powerlessness among community who sometimes lack agency in deciding the parameters of a project.

In my experiences of working in collaboration with First Nation communities, understanding Country through sensing and listening needs to occur much earlier in our processes. Planners need to actively understand the importance of cultural landscapes and how places are connected to one another. This knowledge is harnessed to form the basis of the spatial framework in relation to what types of activities and land uses are appropriate for certain locations. Critically, it is the contributions of Traditional Custodians and Knowledge Holders who provide the instructions to carry out this task.

As a project progresses through its architecture and design stages, the same Traditional Custodians and Knowledge Holders should be taken through the journey to ensure continuity to develop capacities of community for future projects. It is our industry responsibility to understand the notion of reciprocity and actively weave these processes with our own practices to learn and alleviate pressures of consultation fatigue. Activating foundational conversations in the early stages of planning with Traditional Custodians and Knowledge Holder benefitted projects such Gawura and competently moved forward with a First Nations architect.

With understandings of Indigenous cultural intellectual property permissions, industry can transform to facilitate better knowledge-sharing and a transfer of information between disciplines to embed more dynamic and respectful relationships. Our responsibility is to create a more seamless transition between planning and architecture processes to ensure communities participate and contribute is respectful and honouring environments.

We need to navigate all spaces between First Nations communities and the architect and planner. It is important to understand where communities are positioned to lead and take us through the whole project as recommended by Dillon. Gawura is loved and cherished by the local First Nations communities and broader community as a place that connects with Country and allow others to immerse themselves in Country.

Our linear, stop-start thinking between planning and architecture professionals must be transformed so that First Nations communities are participating from the outset of a project. This continuous thread of Country through culture and community enables seamless connections between the different scopes and stages of a project lifespan.

To truly start with Country and embed thinking into the built environment we must consider opportunities for reciprocity with Country, community and culture as foundational to industry practice. For First Nations peoples, reciprocity is a core cultural value, the concept of sharing and exchange, respect and fairness, give and take.

Every piece connects as an interwoven tapestry. Built environment practitioners can understand that starting with Country means transformative shifts in thinking and approaches to generate mutually beneficial outcomes for Country, community and culture.

Elle Davidson is a Balanggarra woman from the East Kimberley and descendant of Captain William Bligh, and describes herself as being caught in the cross-winds of Australia’s history. With a passion to empower the voices of First Nations People, Elle combines her Town Planning and Indigenous Engagement qualifications to shape our places and spaces. Through her approach, she creates a strong platform for Aboriginal voices in the planning process and builds allies to advocate for community. She is the Director of Zion Engagement and Planning, an Aboriginal training and consulting business and an Aboriginal Planning Lecturer at University of Sydney.