The impact of housing on street character and urban liveability

Words by Koos de Keijzer and Gemma MacDonald

Our cities have been witnessing a gradual shift, a transformation embracing more diverse typologies and design solutions with a welcome focus on residents’ quality of life, community engagement and social inclusion. This wave of change is making our inner-city suburbs more interesting, infusing them with a vibrancy.

This is also changing the middle ring and greenfield suburbs; however, the missing middle has been challenging to deliver and remains largely absent in our large urban centres. Planners in Australia have driven the concept of active edges as buildings touch the ground wherever they may be. One unfortunate by-product of low Australian residential densities is that active edges have become retail edges because retail is considered active, but is it? A quick look at Melbourne’s Docklands precinct shows at least 1.8 lineal kilometres of empty retail, providing no activation on the street. With Australia’s rapidly changing consumer landscape, retail as the active edge is becoming challenged.

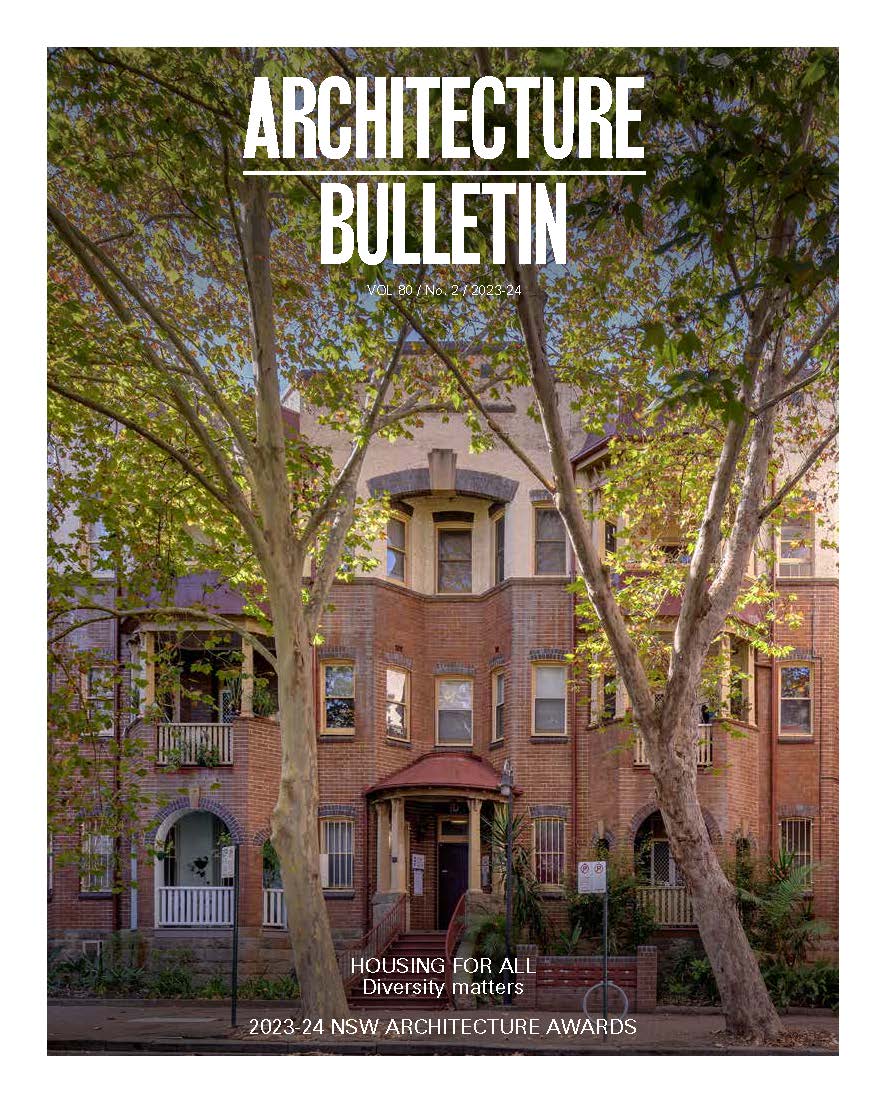

Australian suburbs’ physical, architectural, and social fabric has been undergoing a fascinating metamorphosis. The reuse of stoops has breathed new life into otherwise mundane neighbourhoods, taking cues from the architectural technique of the stoop, widely used in North America and Europe. Stoop, a small porch, comes from Dutch stoep and was fundamental in the early construction of New York City. The stoop technique has been used significantly, for instance, in Paddington, East Melbourne, and Surry Hills. Stoops serve as a transitional space between the public street and the private interior of a building. This can create a sense of privacy and security, Jane Jacob’s “eyes on the street” while maintaining a connection to the street. Our projects, Arkadia and Eve in inner-city Sydney, with their contemporary interpretation of the stoop, have been instrumental in activating ground-level spaces in those areas. They have turned otherwise defunct sites into hubs of activity. Stoops promote social interaction between neighbours and passersby. People often sit on their stoops, allowing for impromptu conversations, neighbourly interactions, and a sense of community, creating passive surveillance where a community thrives.

Focusing on communal sun-soaked spaces to the north, Arkadia encourages a connection to the local community through extensive gathering spaces and small-scale entrances. Landscaped through-links and an integrated public pocket park seek to give something back to the wider community. These spaces encourage chance meetings across the site while maintaining key pedestrian links to Sydney Park and beyond. The idea of the street as a social space is exemplified by the Dutch Woonerf, roughly translated as “living streets,” functions without traffic lights, stop signs, lane dividers or even sidewalks. The whole point is to encourage human interaction; those who use the space are forced to be aware of others around them, make eye contact and engage in person-to-person interactions, a tactical more holistic urbanism.

A preference for city living has led to a rise in compact and efficient housing designs, particularly in major cities. Compact apartments, townhouses, and smaller single-family homes are popular due to limited space and high property costs. High-rise solutions to city living have arguably contributed to a reduction of ground level culture, stoops replaced by empty commercial space. The humble terrace is the typology that adds the most diversity and activation to our streets and communities. Their charm is their close connection to the street, with minimal setbacks that maximise their impact on street character and visual reference. To mimic this, front setback variance can modulate the built form to add to the streetscape. Our Lumina project in Penrith, NSW has a deliberate modulation of its architectural structure, front setbacks are strategically diverse throughout the building’s length. This effectively divides the building into several visually distinct components, each characterised by unique architectural features. The outcome is a vibrant and dynamic streetscape that gives the impression of numerous individual smaller structures, rather than a single, unvarying monolithic form.

Australian suburban areas tend to have more spacious streets and a layout that allows for larger lots and more spread-out housing. Due to limited space, European houses often have compact gardens or courtyards. The denser approach prioritises street-level activation while maintaining the residential generosity of areas. The diversity here isn’t limited to mere aesthetics; it encompasses a socio-economic spectrum, reflecting the multigenerational dynamics of changing families and shifting priorities driven by housing affordability.

Increasingly, households accommodate multiple generations under one roof, necessitating flexible housing designs. Designs that allow for separate living spaces or granny flats are in demand to facilitate multigenerational living as the population ages, with limited options for senior living or aged affordable care accommodation. Designs must cater to the needs of different household sizes and compositions by providing a mix of one, two and three-bedroom apartments, making it more inclusive and accessible to a diverse range of tenants. Increasingly, development is tenure blind – a principle that minimises the stigma attached to subsidised housing, reduces the likelihood of local problems connected to tenure and increases the probability of a socially cohesive community.

As small backyards or dwellings without backyards become more common, parks and public green spaces become critical in providing places for people of all ages to be active. Walkable, connected and attractive neighbourhoods create great cities. Large-scale masterplans now prioritise linkages at the ground level, weaving a fine-grain tapestry that contributes to a sense of diversity and interest. It’s not just about increasing density; it’s about creating engaging, permeable spaces providing accessibility and amenity that enrich the lives of residents and create a sense of place and its identity.

The ongoing transformation of Australian cities and suburbs seeks to create more inclusive, engaging, and vibrant communities that cater to their residents’ diverse needs and preferences. This shift reflects a commitment to enhancing the quality of life and social wellbeing for all members of these evolving urban landscapes.

Koos de Keijzer, DKO principal, leads a 250+ strong team across Australia, New Zealand, and Southeast Asia, excelling in urban design, architecture, interiors, and landscape architecture. His dedication to sustainable communities is evident in his impactful projects and consultative role with various city councils. He studied at Eindhoven University of Technology, Netherlands.

Gemma MacDonald studied anthropology at Goldsmiths, University of London and has a wealth of experience in design management in the UK and Australia. She is currently the studio manager for DKO in Sydney.

More from Architecture Bulletin

Bangkok Apartment and Chonburi Multi-Purpose Building: Suphasidh Architects

Burudi Gurad, Burudi Ora: Critical spatial, relationalities of care

Wattleseed: Scott and Ryland Architects

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.