The architecture of housing: Obligations and opportunities

Words by Philip Thalis

Australia has long been categorised as one of the most urbanised nations, with a high percentage of the population living in suburbs and conurbations. In recent decades, a substantially greater proportion of people are now living in higher density housing. This is certainly the case in major cities like Sydney and Melbourne, where over 50% of all new dwellings have been in the form of apartment buildings. As denser forms of housing are now prevalent across Australia, the profession must rise to the challenge and must better demonstrate the role and character of such housing in city making.

Philosopher Henri Lefebvre articulated an essential democratic agenda for urban culture. “The right to the city manifests itself as a superior form of rights: the right to freedom, the right of the individual to take part in society, the right to habitat and to inhabit. … to participation and appropriation (clearly distinct from the right of property), are implied in the right to the city.”1

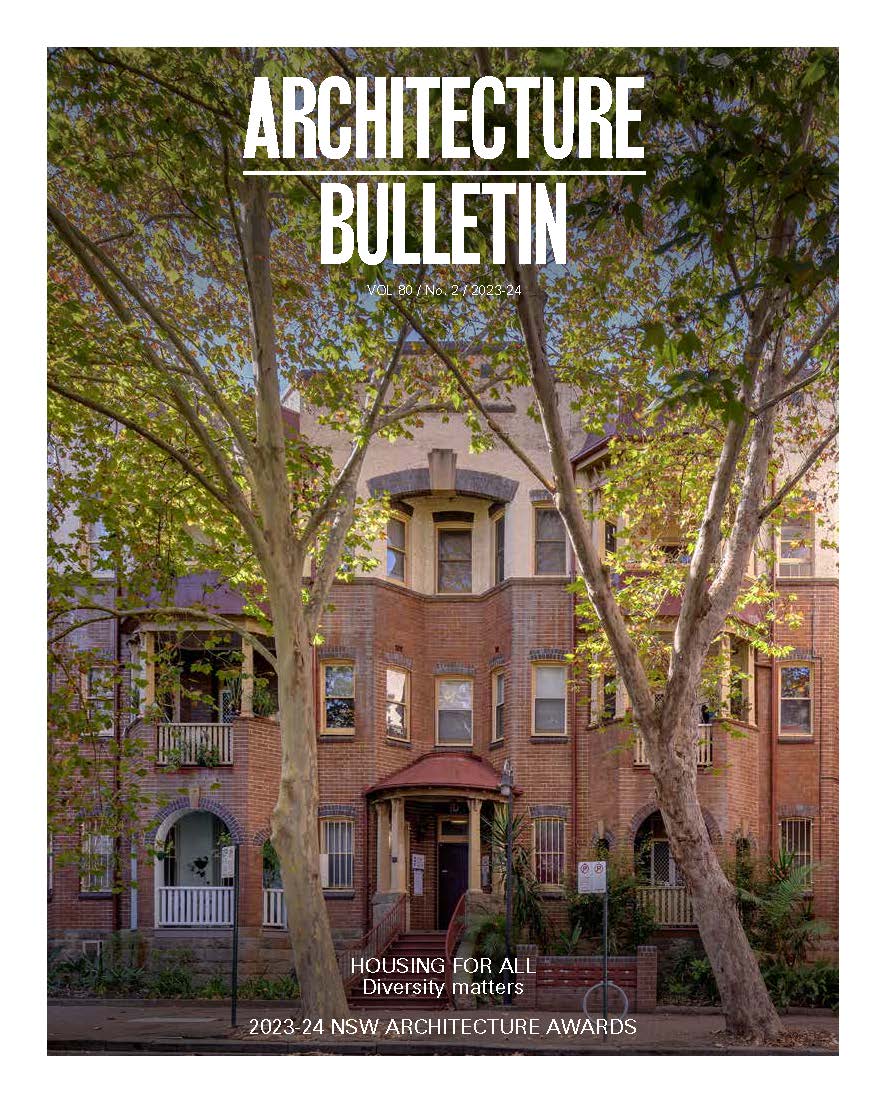

In these terms, the intensification of urban housing matters to us all. To the existing city, it brings a new scale and street character, infusing places with more people and activity. For new inhabitants, it brings more compact urban living, with the benefits of proximity and the buzz of denser neighbourhoods. The design of this new generation of buildings will affect everyone.

The city manifests itself as a continuum of social, economic, political and technological forces which shapes housing types, and in turn is shaped by that housing. Mass housing, be it the serial terrace houses of the 19th century, the idiomatic single house sprawl of the 20th century, or the looming apartment buildings of the 21st century so far, can propel the evolving urbanity of our cities. With few exceptions housing constitutes the major proportion of any city’s urban footprint and building stock, and as such it carries a responsibility for architectural intelligence.

The time spans of city making need to be understood; urban layouts persist sometimes for millennia, subdivisions over centuries, housing types for many decades as a minimum. People live in dwellings, sometimes for their whole life, that were never specifically designed to their needs or wants. They adapt to their selected urban habitat as much as they adapt the housing itself, as people’s housing choices are always an amalgam of price, size, location, lifestyle and time of life. The qualities of housing always have a direct correlation to the everyday life of residents.

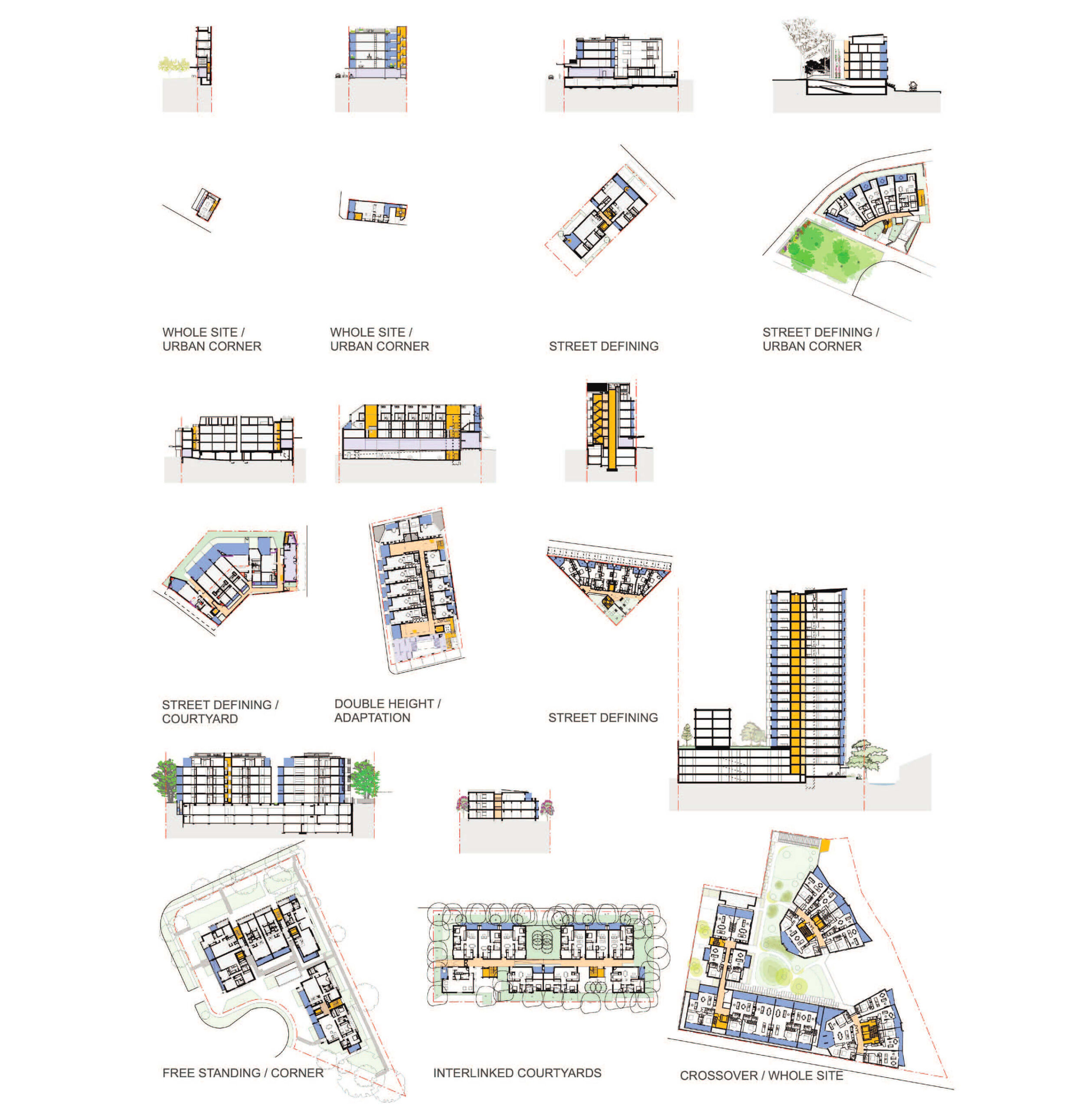

The attributes of good housing traverse civilisations and span eras. The architecture of housing has specific disciplinary knowledge, acquired through study of precedents and work on projects. Increasingly it is burdened by a myriad of prescriptive unintegrated regulations and codes. If housing can claim any specific theory it would centre on distinctions of generative models and generic types2, and more recently hybrids spawned by combinations of program, ownership structure and scale. Type is essentially defined by the residents’ daily trajectory from the private world of the apartment interior – through to the communal and circulation spaces, within the boundaries of its lot – to the relationship to public street and out to the wider city. Organisation and distribution are the key determinants of type, to be adapted and reinterpreted in response to each site’s specific situation and dimensions, determining its architectural proposition open to the city.

The challenge for the architecture of housing is to imbue inert quantities with vivid qualities. By design, these qualities must have visceral, physical, green dimensions – uplifting the experience of daily life. The need for amenity and environmental performance are fundamental and have long been understood, as Renaissance architect LB Alberti wrote in the 15th century: “it would be convenient to have glass windows, balconies, and porticos; apart from the attraction of the view, they may admit sun or breezes, depending on the season… The ancients preferred their porticos to face south (north in the southern hemisphere), because in summer the arc of the sun would be too high for its rays to enter, whereas in winter it would be low enough.” Such a timeless reminder on housing design.

Due to their size and growing complexities today, most apartment buildings are designed by architects – indeed in New South Wales it is a requirement unique in Australia. This is the profession’s significant opportunity for city making, marking architects’ responsibility to society to realise good housing. Rather than conceiving of housing as a commodity like any other, the obligation for all involved in the design of housing must be to deliver as good a place to live as possible – a place with character and amenity, affording dignity, connected to landscape, made of durable construction, capable of personalisation. Now we must also add, minimising embodied energy and mitigating climatic change.

Urban housing has often been associated with accelerated periods of urban transformation, propelled by economic and social forces. Unsurprisingly housing’s role in city making is a barometer of each era’s many pressures and threats. Of today’s threats, Saskia Sassen sharply observed: “The spread of mega-projects with vast footprints that inevitably kill much urban tissue…density is not enough to have a city.”3 Pertinent to the media and real estate fertilisation of Australian architects’ up-market houses, David Madden & Peter Marcuse critiqued over-capitalised housing conceived for speculation; “Plenty of super-prime real estate should barely be considered housing at all… luxury housing is antisocial.”4 In contrast to bespoke houses, the economy of space and means has long been characteristic of mass housing.

Unquestioning subjugation to economic determinants has never been good enough – clearly it is unconscionable now. Our opportunities must be underpinned by discriminating study of the substantial body of architectural knowledge and practice specific to urban housing, propagated by discussion and shared ideas, tested through projects, publication and exhibitions. As architects our pressing obligation is to contribute to an enriched culture of city making that uplifts daily life, prioritises environmental performance and the equitable availability of the architecture of housing.

Notes

1 Henri Lefebvre, La droit a la ville, Editions Anthropos, 1972. (English translation: Eleonore Kofman and Elizabeth Lebas, Blackwell, Oxford, 1996) pp173-4

2 See Quatremere de Quincy discussions of type

3 Saskia Sassen, “Who owns our cities – and why this urban takeover should concern us all” https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2015/nov/24/who-owns-our-cities-and-why-this-urban-takeover-should-concern-us-all

4 David Madden & Peter Marcuse, In Defense of Housing; The Politics of Crisis Verso, London 2016 pp37-38

Philip Thalis is founding principal of Hill Thalis Architecture + Urban Projects and holds a professor of practice in architecture at UNSW. Hill Thalis is recognised for its design and independent standpoint. The practice has designed more than 100 apartment buildings of varying types and scales.