Revisited: Some aspects of housing overseas

Simon Goddard and Katherine Sundermann

In 1958, Victorian Housing Commission officials headed out on a global study tour. The goal was to find an urban cure for the slums in inner Melbourne. The report, Some Aspects of Housing Overseas, catalogued their lessons. This would become the blueprint for 47 Housing Commission towers and numerous two- and three-storey walk-ups.

But if the towers were the answer, what was the question? It wasn’t about cost. The elevators made the tower apartments more expensive to build than their low-rise counterparts. The Housing Commission towers were a bold statement about quality of life, and how to provide it. Headstrong, tone deaf, ambitious, derivative. The towers signalled an era where modular building construction, cutting-edge vertical circulation and powerful public finances were aligned towards the singular noble goal of improving dwelling amenity for working class inhabitants and recent migrants.

And now, with more funding available than we’ve seen in a generation, there is the will to reimagine these sites. Architects, urban designers and public servants have duly taken up the subject. But, how to frame the problem?

Turning around the tower

How did a country obsessed with the backyard conclude that these new innovative towers should include no private outdoor space? Built with post-tensioned prefabricated technology, the Housing Commission stack-of-cards towers will be unlikely to collapse, unlike their equivalents in the UK. In the UK the panels are merely bolted together and have proven highly dangerous, as evidenced in the 1968 Ronan Point flats disaster, where four people died as a consequence of a gas leak. In Australia, the panels are tied together with post-tensioned cables, making them much more secure, but also fiercely resisting any attempts to be adapted.

In 2008 an architectural competition, Tower Turnaround, attempted to address the deficiencies of the towers. Well-detailed, cantilevered and costly – but with no balcony – the winning prototype pod by BKK and Peter Elliott Architects was a one-off. A solitary pod was added to the facade of a T-tower in Gordon Street Footscray.

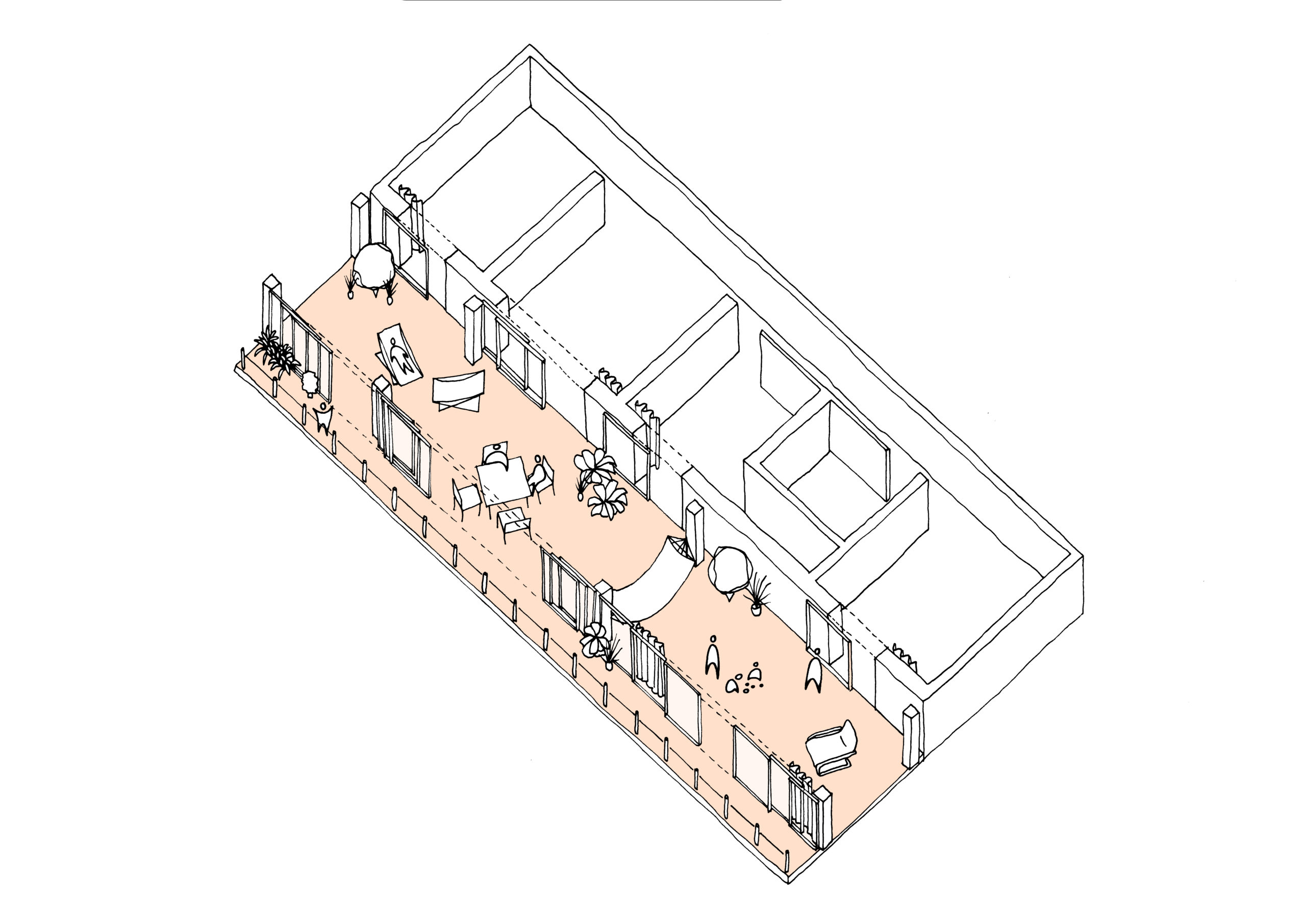

Thirteen years later, Lacaton Vassal would win the Pritzker for a similar concept. Their innovation was to provide an inexpensive extension with undefined use, allowing residents to appropriate as they saw fit. The model has now been rolled out across four estates and over 600 dwellings. Our current tower residents have no balconies, which was brought into sharp relief with the COVID lockdowns. How can we turn this around?

Modernist Dream Over?

Le Corbusier’s dream of towers in parkland, with no need for the messiness of streets and laneways arrived in Melbourne – 40 years late. A decade later in the 70s, the Carlton Association in an alliance with the unions put a stop to the slum clearance halting the demolition of 200 acres of terrace houses in Carlton. Today, fences and ‘tenants only’ signs tend to keep people away from the grass and playgrounds between the buildings. Money has been found to add new homes to this prime real estate as the waiting list for public housing grows longer. Some have suggested that we take down the fence and share the open space.

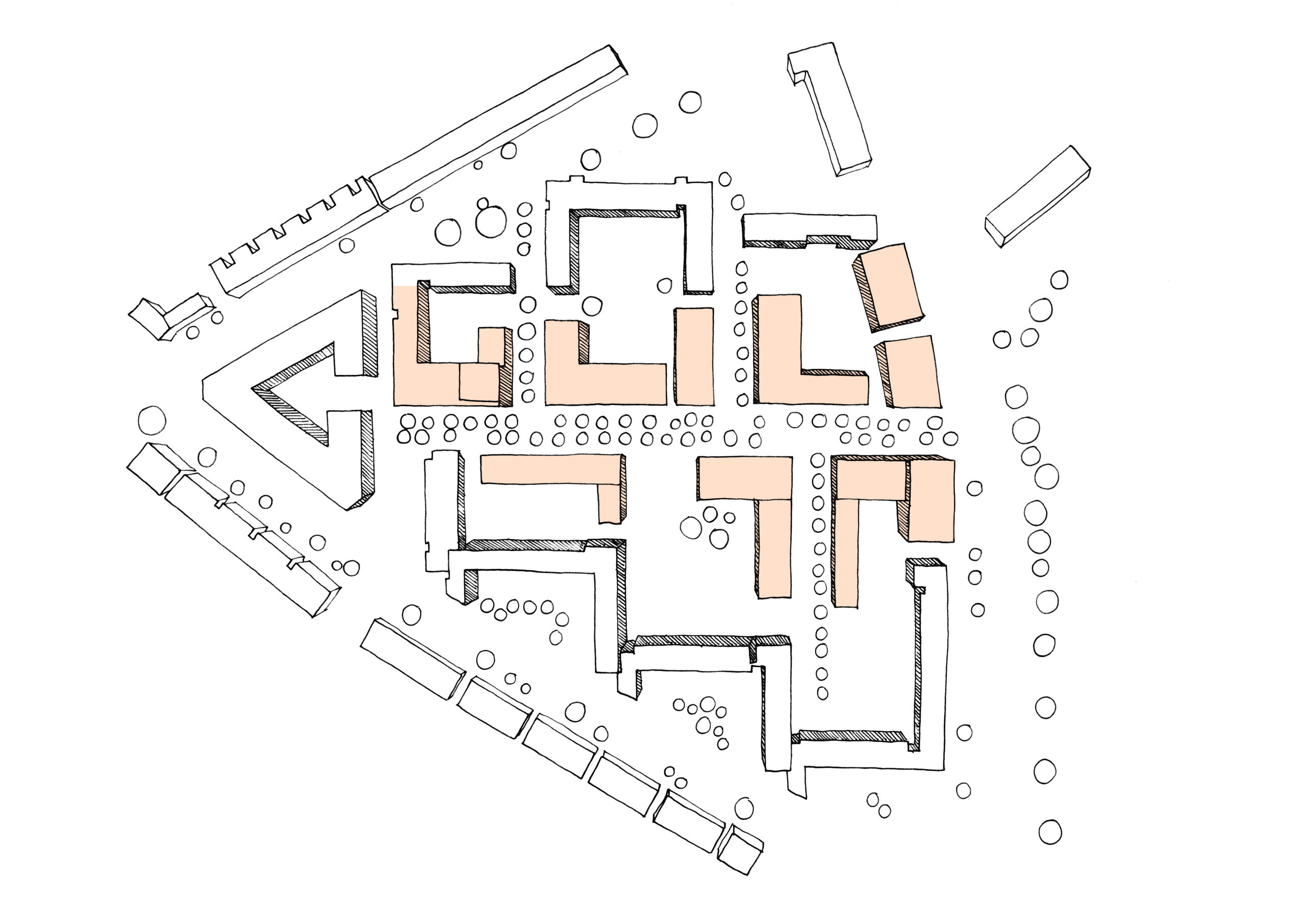

Do we integrate the towers like Kings Crescent in London by Karakusevic Carson Architects? Or do we risk cementing in the underperforming towers, with forgotten residents looking down on high performing homes? If the towers were to reach the end of their structural life, what neighbourhood do we envision in their place? What shared uses do we build back, aside from housing, to create one community instead of two to lessen the social divide?

Resident knows best

At ArchiPitch (March 2021) Mark Feenane from the Victoria Public Tenants Association told of a man, homeless for most of his life, who was distraught when he arrived in his brand-new social housing eco-apartment. The one thing he had been waiting for after many years on the streets – air-conditioning – wasn’t there.

With all the best intentions, social housing is at risk of paternalism. But how can we know best with such a diverse spread of occupants? At Îlink in Île de Nantes, future residents and business owners worked together for years to negotiate their future neighbourhood. Shared community gardens, event spaces and workshop spaces were negotiated, collectively preparing for the community life that will take place there.

Why not invite future inhabitants to participate in design, given their deep knowledge of how they would like to live? Given the complexities of these sites and their residents, how could a stronger community be built through the process of consultation?

This scale of investment promised hasn’t been seen since the Housing Commission was at its peak. The need is as great, and the level of ambition is as high. There is a generation of knowledge in social housing repair in northern Europe. What can be translated, and what risks repeating the audacity of the original plan? Given the high stakes, we should start by asking the right questions.

Simon Goddard is an independent urbanist, researcher and designer based in Paris. He has collaborated on social housing regeneration projects across France. Simon has work for public and private sectors, in Melbourne, Copenhagen and Paris, and projects have ranged from industrial design through to strategic planning, with a principle focus on urbanism. He approaches projects through careful analysis of context, and with special attention to human scale.

Katherine Sundermann is an Associate Director at MGS Architects, leading masterplan projects for universities, creative employment areas and housing precincts. She is also a studio leader at Monash University, helping inspire the next generation of public interest urbanists. Drawing on her experience working as an architect and urban designer in Australia, Germany and the Netherlands, Katherine is passionate about increasing housing diversity and quality in Australia, to help create more diverse and inclusive neighbourhoods.