Architecture has the potential to contribute positively over the next few decades as humanity adapts to the changing world we have co-created. While the resilience of our current building stock is poor, we have an opportunity to improve it and create new buildings that are appropriately resilient to the future we face.

Responses to climate disasters, unsurprisingly, garner most attention and while incredibly important they only tell part of the story. Buildings that resist the physical impacts of fire, flood and storm are required in certain locations, although there will be increasing calls to retreat from some, yet many places will not be impacted in these ways.

The chronic stresses are ones that will be more geographically dispersed – increasingly long and intense heatwaves and, as we saw in 2019/2020, the impacts of bushfires significantly beyond the fire front itself.

The role of architecture positively impacting on the health of a building’s occupants would be one measure of success. Responding to the climate crisis presents the opportunity to not only address these newer stresses but also to remedy those previously created.

Historically, and even today at a residential scale, architecture has relied on natural ventilation for maintaining indoor air quality. While effective when conditions are favourable, it is a driver of poor outcomes in many situations.

Airtight, appropriately ventilated buildings provide great indoor air quality year-round while also allowing for natural ventilation when the external environment is desirable. Increasingly in Australia, architects have been embracing the Passivhaus standard as a low risk, high-reward pathway to delivering health and comfort for their clients.

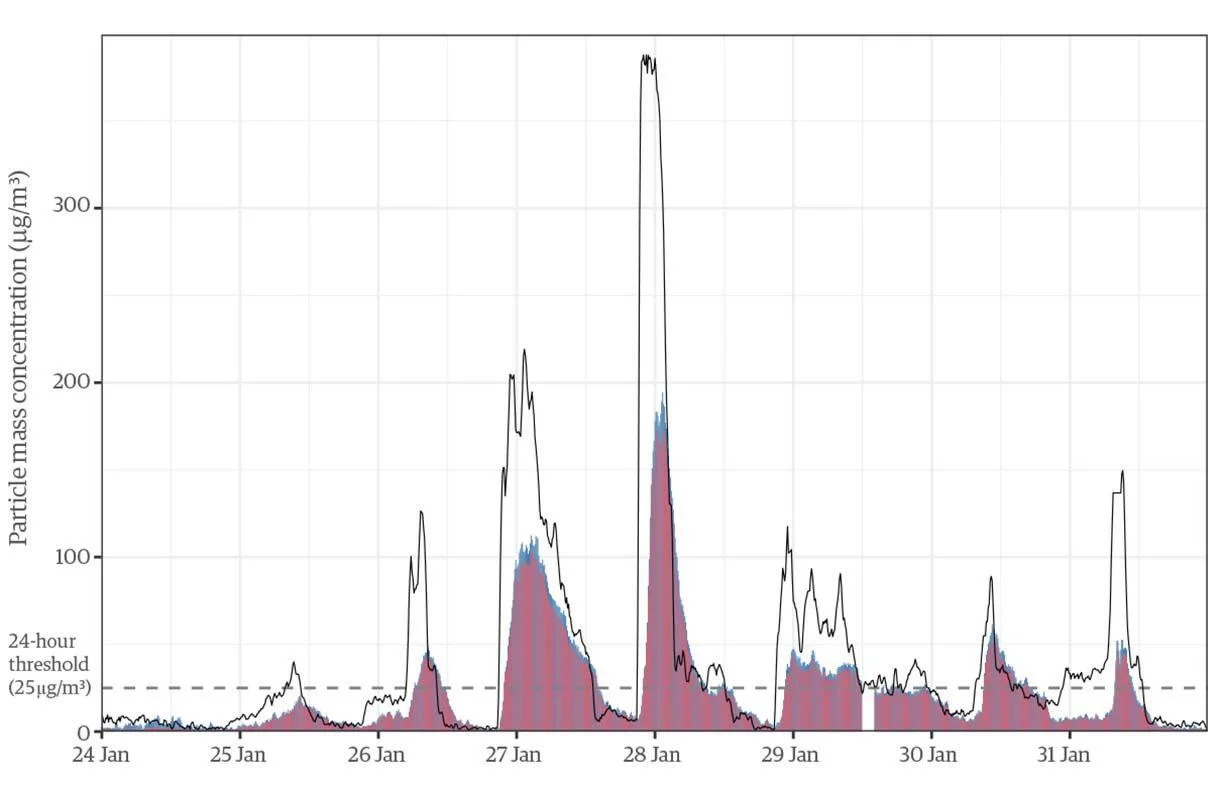

The data above shows the impacts of airtightness and ventilation in dramatically reducing the inflow of particulate matter (PM2.5 and smaller) into a Canberra home during the Black Summer bushfires. (The black line shows outdoor PM2.5 concentrations; coloured areas show indoor PM concentrations—red < 1 micron, blue 1.0 to 2.5 microns.) Many Passivhaus projects now have additional HEPA filters that can be easily inserted during smoke events to further reduce indoor pollution.

While focus on extreme events garners attention, some existing stresses are far less publicised. Australia has the highest prevalence of asthma in the world and while the causes are varied, poor indoor air quality is a factor.

As this article reaches you, winter will be setting in and many will be remembering that even in our own wonderful state [NSW] it does get cold, if only for a few short months. With most older homes not being fully heated, most are not consistently warm nor inadequately insulated. The cold surfaces of the walls befriend warm, humid air and condensation and/or mould. Instinct prevents people from opening windows due to cool outdoor temperatures, resulting in increasing humidity levels (from breathing, cooking, showering) which exacerbates the impacts.

While higher humidity may cause mould where the surfaces are cool, for those wealth enough to afford the energy bills, this can be avoided by heating rooms sufficiently regardless of the building’s levels of insulation and ability to retain that warmth.

Unfortunately, the lack of reliable ventilation also causes carbon dioxide levels to rise – 1000ppm is generally accepted as a maximum for good indoor air quality. Research on my own house showed that a non-mechanically ventilated bedroom in a leaky (10ACH50) house can reach 2400ppm overnight. Data from the monitoring of various schools shows classrooms reaching over 5000ppm.

Mechanical ventilation and secondary glazing have provided a temporary fix for my child’s room, yet it is not a holistic or efficient solution. The Passivhaus standard with its interrelated principles of airtightness, insulation, appropriate windows and shading, minimisation of thermal bridges and mechanical ventilation underpin my strategy.

When implemented consistently, these principles deliver not only healthy and comfortable homes but also efficient ones. Airtightness equals control which you would think could appeal to the stereotypical architect! However, choosing some principles while ignoring the others, will have undesirable consequences, as decades of building science have shown.

As the global response to the climate crisis evolves, the smarter reactions have been blending mitigation and adaptation. Low energy buildings are a critical aspect of mitigation and net zero buildings are a subset of those when appropriate amounts of renewable energy generation are paired with them. It is important to remember that resilience is not net zero but it is an appropriately performing thermal envelope. Solar panels alone will not save us.

The UK cities of Exeter and Norwich have been leading the way. All new social housing constructed is now designed and built to meet the Passivhaus standard. In 2019, the Mikhail Riches designed Goldsmith Street Housing took out the Stirling Prize, RIBA’s highest accolade.

The climate crisis is an opportunity for architects to equip society with the best chances of success. We can embrace the (building) science and apply our skills to create a beautiful future that allows us all to thrive; the data has been in for decades. Can we please accept it as we have accepted gravity and create the future we need – everything, everywhere, all at once.

Andy Marlow RAIA is a director at Envirotecture.