Recalibrating cultural awareness expectations for architects working in Australia

Words by MICHAEL MOSSMAN, KIRSTEN ORR & KATHLYN LOSEBY

THOUGHTS ON THE 2021 NATIONAL STANDARD OF COMPETENCY FOR ARCHITECTS

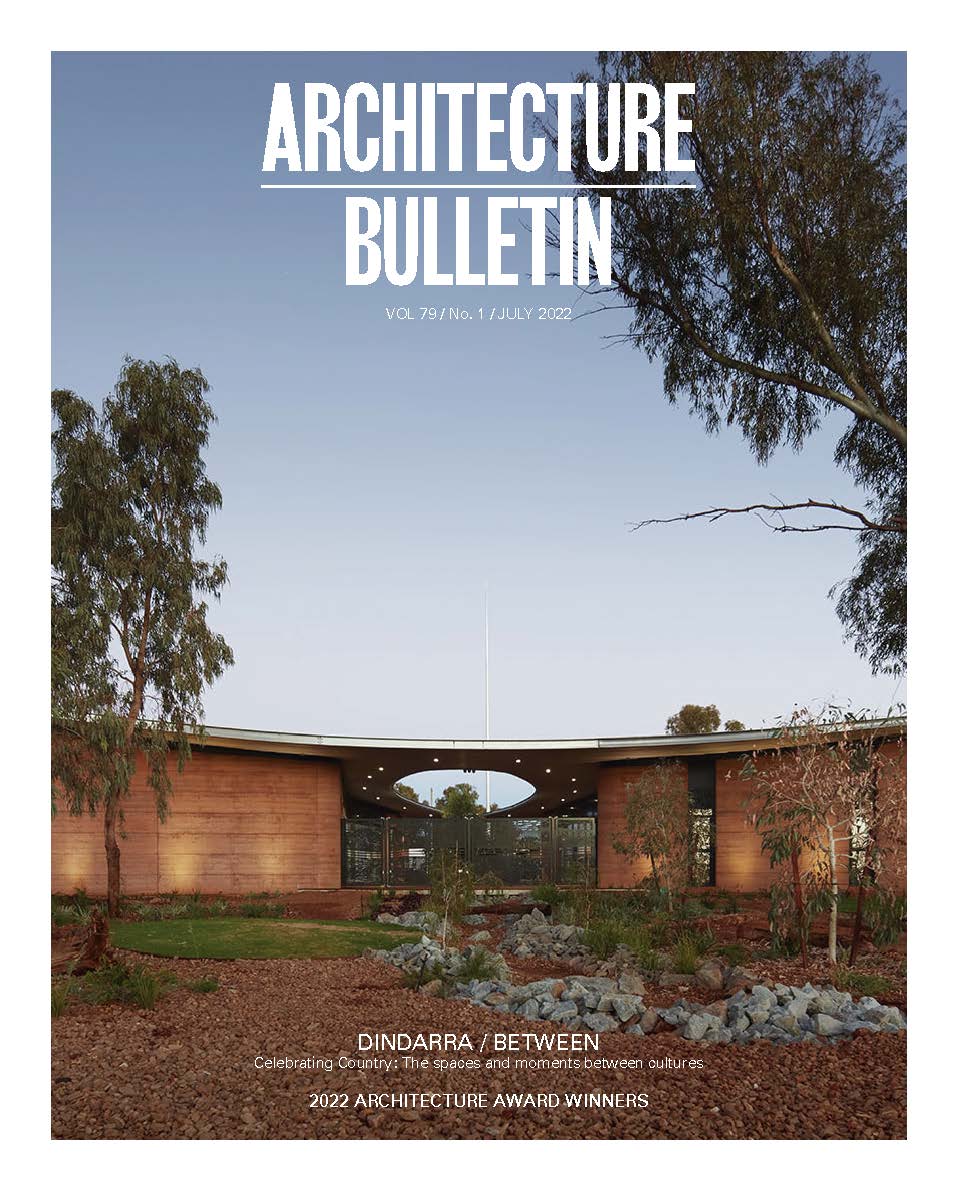

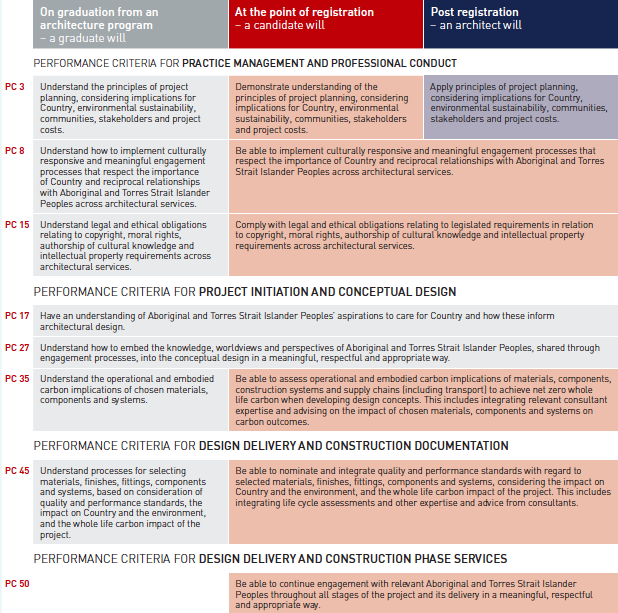

The 2021 National Standard of Competency for Architects (NSCA)1 identifies the skills, knowledge and capabilities required for the general practice of architecture in contemporary Australia. Significant new content is introduced in new Performance Criteria (PCs) focused on engagement with First Nations peoples and understanding and respecting Country.

For the first time since its introduction in 1993, this fifth edition of the standards includes eight PCs that recalibrate the cultural awareness expectations of all Australian architects and that present ground-breaking opportunities for the profession to work in meaningful ways with Country and First Nations Cultures and Communities. This is a remarkable transition, given the failure of previous standards to account for Country and local Indigenous cultures. The new competency expectations of the 2021 NSCA are long overdue and an exciting, optimistic commitment by the profession for lasting change.

This article results from a conversation between us2 about the inclusion of Country, First Nations Cultures and Communities in the 2021 NSCA and the likely profound, long-term changes it will bring about in the capability expectations of Australian architects and architecture graduates. The eight PCs were developed and finalised by the Australian Institute of Architects First Nations Advisory Working Group and Cultural Reference Panel chaired by Sarah Lynn Rees and Paul Memmott.3

With this structural reform, the architectural profession cannot continue to accommodate ignorance of Country, First Nations Cultures and Communities. For to continue without addressing this knowledge gap is to suggest that architects as a profession accept having less knowledge, learning or information than is expected by the wider society.

The new PCs will ensure a continuing building and expansion of knowledge by Australian architects to establish a profession-wide uplift in capacity that addresses critical knowledge and skill gaps. All architects must accept that there is much we do not know in the profession when it comes to architecture interacting with Country and First Nations Cultures, and Communities at practical and structural levels of engagement.

The development of national competency standards for Australian professions was one of the key features of the Hawke Government’s approach to federal microeconomic reform in the late 1980s to early 1990s. At that time, it

was intended that competency standards for architects would be applied to those seeking registration as an architect in Australia but would not form part of the state and territory legislation controlling the registration of architects or be applied to architectural education.

Since the first publication in 1993 of NCSA 01, the competency standards have evolved, and their authority and application has expanded. Today, they underpin all AACA competency-based assessment pathways to registration – defining the skillset expected of architects entering the profession – and they are embedded in accreditation procedures for Australian architecture programs – informing higher education curricula to directly shape the architects of the future.4

With the publication of the 2021 NSCA and its full implementation in assessment pathways leading to registration and university accreditation procedures, transformation of mainstream architectural practice is expected to flow to all participants in the wider architectural services industry. The eight PCs that specifically focus on Country and First Nations Cultures and Communities (PC 3, 8, 15, 17, 27, 36, 45 and 50) ensure that all architects have the knowledge, understanding and skills necessary to deliver professional services in line with societal expectations. Yet in implementing these new PCs, the architecture profession is proactively setting broad-reaching expectations that are missing in the regulatory regimes of other disciplines such as planning.

Because the competency standards exist at a national level and sit outside state-based legislative processes, some architects might be tempted to argue that the 2021 NSCA is not relevant to them and the architectural services they provide. Such claims are insupportable in light of contemporary expectations of architects to be competent in their appreciation of differences and commonalities between cultures that enrich the qualities of placemaking in Australia. For example, academic and industry interactions with frameworks such as the NSW Government Architect’s Connecting with Country Draft Framework are now the expectation in public infrastructure design and not optional.5

In turn, Connecting with Country processes are increasingly demanded in private projects to enrich the quality of the design legacy for consumers. Moreover, the 2021 NSCA is indirectly referenced in the regulation of architects through annual Continuing Professional Development (CPD) requirements. In NSW, for example, clause 16(1) of the NSW Code of Professional Conduct requires an architect to “take all reasonable steps to maintain and improve the skills and knowledge necessary for the provision of the architectural services that the architect normally provides” and CPD policy of the NSW Architects Registration Board requires architects to refer to the NSCA as the basis for “an effective CPD regime”. As such, all architects will be captured in the exciting conversations to unfold around Country and First Nations Cultures.

It is thought provoking to contemplate how the new PCs will transform interactions between consumers and Country and First Nations cultures relational to place. There are many opportunities to connect the differences and commonalities between Country and First Nations knowledge systems and the normative Western tenets of architecture and placemaking.

Nevertheless, it is impossible to pinpoint exactly where the 2021 NSCA could take us in transforming how architectural services are procured. It is critical that we understand that individuals across the wider architectural services industry will be engaging at different levels of knowledge and through various intensities of experience and application. The issues are further intensified by adding the important qualities of First Nations community interactions as part of the PCs.

These interactions with Communities skilled in translating and storytelling Country and local Cultures are refreshing additions to the structural nature of architectural practice. Importantly, careful considerations of cultural and moral competence, faculties of knowledge exchange between cultures, appreciations of deeply embedded intergenerational trauma and the realities of consultation fatigue require skilful articulation throughout the project process.

It is up to individuals in the architecture profession to learn, collaborate, build capacities and focus energies to meaningfully interact with the specific Performance Criteria as conscious commitments. Energising ourselves to become cognisant of the 2021 NSCA structural reforms to enhance the quality of placemaking on Country and activate more inclusive interactions with First Nations, Cultures and Communities will result in improved living environments. We are optimistic that these are actions and legacies we can all look forward to in the future.

NOTES

1 AACA (2021), National Standard of Competency for Architects, accessed 27 May 2022: https://aaca.org.au/national-standard-of-competency-for-architects/2021nsca/

2 Dr Michael Mossman (Lecturer University of Sydney School of Architecture Design and Planning), Dr Kirsten Orr (Registrar NSW Architects Registration Board) and Kathlyn Loseby (CEO Architects Accreditation Council of Australia (AACA))

3 https://www.architecture.com.au/about/national-council-committees/first-nations-advisory-working-group-and-cultural-reference-panel

4 Orr, K (2015) ‘Institutionalising National Standards: A history of the incorporation of the Architects Accreditation Council of Australia (AACA) and the National Competency Standards in Architecture (NCSA),’ Australian Institute of Architects, Architecture.com.au https://www.architecture.com.au/wp-content/uploads/Institutionalising-National-Standards_Kirsten-Orr_2015.pdf

5 https://www.governmentarchitect.nsw.gov.au/projects/designing-with-country

Dr Michael Mossman is a proud Kuku Yalanji man, born and raised in Cairns on Yidinji Country. He now lives and works on Gadigal land and is an academic lecturer and researcher at the University of Sydney School of Architecture Design and Planning where he was recently awarded his Doctor of Philosophy with the topic of his thesis: ‘Third Space, Architecture and Indigeneity.

Dr Kirsten Orr is Registrar of the NSW Architects Registration Board and a Director of the Architects Accreditation Council of Australia. Kirsten is a NSW registered architect. She has served on two national panels to review the National Standard of Competency for Architects (NSCA) in 2006-08 and 2020-21. In 2015 she led the development of the Australian Architectural Education and Competency Framework that made nationally significant policy recommendations on the interpretation and implementation of the NSCA for the accreditation of architecture programs.

Kathlyn Loseby is Immediate Past President of the NSW Chapter of the Australian Institute of Architects and CEO of the Architects Accreditation Council of Australia.