Australia is in a housing emergency. Facing a situation of such complexity and scale, it is important to remember the human impact of inadequate safe housing. Whether that be families sleeping in their cars, the increasing number of working homeless, or people forgoing medical expenses to afford housing.

A problem built over decades; the housing emergency will take decades to fix. There is no silver bullet. While increasing supply is touted as the solution, the construction of new dwellings alone does not deal with the immediacy of the issue. If not solved quickly, the housing crisis will rapidly become a homelessness crisis.

With over 57,000 households in NSW on the social housing waitlist1 and 2700 social housing dwellings sitting empty across Sydney,2 immediate wins are possible.

The refurbishment and infill of existing social housing, as an alternative to its demolition and reconstruction, presents a fast and scalable way of providing housing while achieving better social, economic, and environmental outcomes. The method is in direct opposition to the prevailing paradigm condemning buildings to be single use at the end of their design life, or worse yet, when no longer considered in vogue.

At a higher level, the attitude towards consumption and disposal has led to a throwaway culture of built form. Across the built environment, expected lifespans of new buildings have reduced by 87 years over the last century.3 With this, the problem becomes twofold: robust buildings are being torn down and replaced with new builds with a shorter lifespan, perpetuating the cycle.

When demolishing and rebuilding social housing, there is reduction in the capacity to house people in the short and medium term. Currently undergoing demolition, Sydney’s Arncliffe estate once accommodated 142 public housing dwellings in double-brick walkup apartments.4 Relocations began in 2018 and, outside of being used as emergency accommodation during the pandemic, many have sat empty for years. In their place 180 new social housing and 564 private dwellings will be constructed, set for completion in 2025.

While not all existing social housing is viable to retain, common justifications to demolish stock are based on a state of disrepair and/or potential to build an increased number of new dwellings.

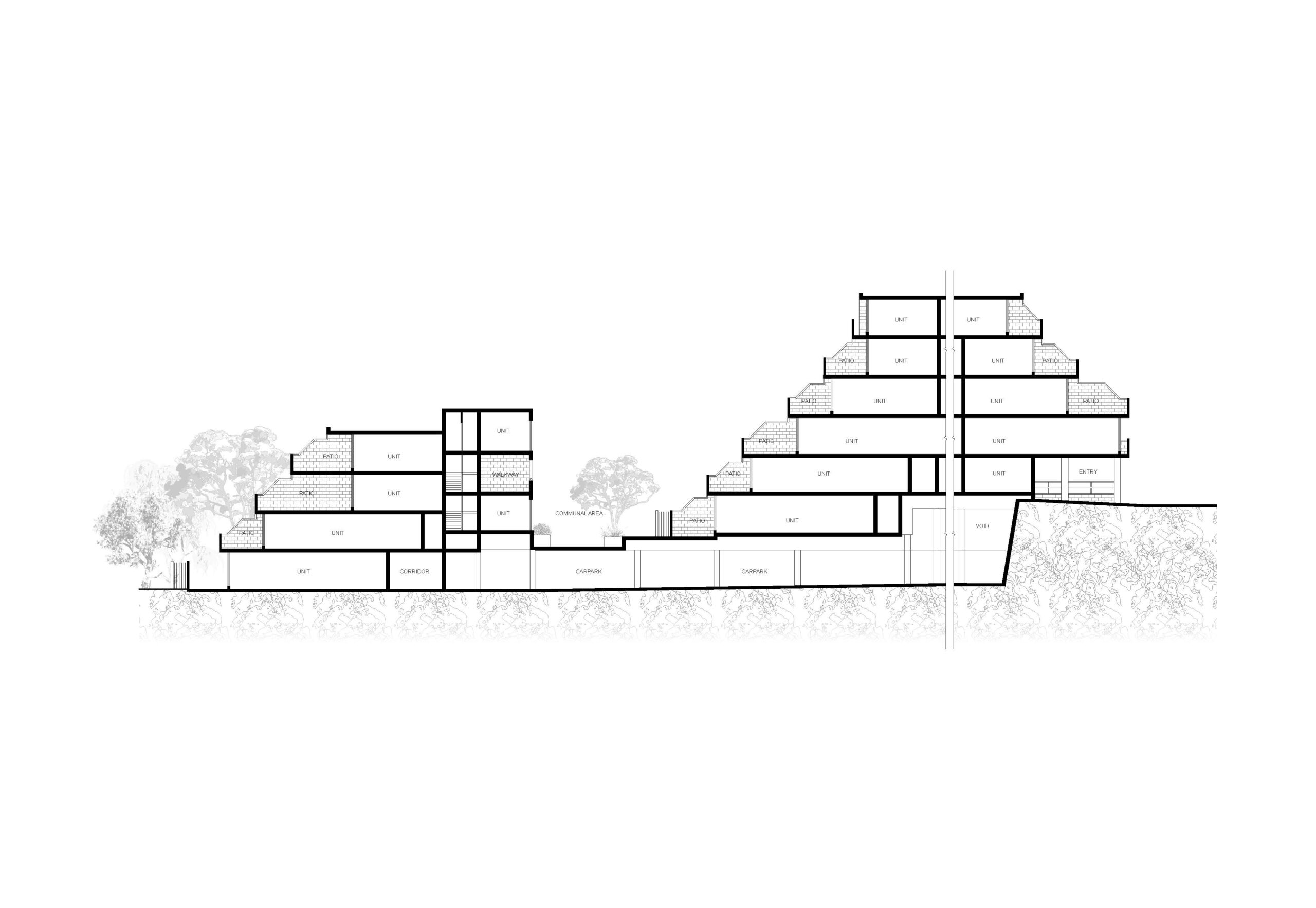

Housing that needs maintenance and upgrading is not an argument for its demolition, rather it presents an opportunity to reinvigorate existing spaces and provide amenity. Required dwelling increase can be achieved through design, examining existing structures and surrounding land to build new homes.

Through the Byera Hadley Travelling Scholarship, I had the opportunity to travel throughout Europe to document examples of social housing refurbishments in a report titled Reviving the Block.5 The practise is not a new concept and has been carried out successfully by multiple European governments. The most prominent examples of refurbishment are the multiple works of 2021 Pritzker Prize winning architects Lacaton and Vassal, in collaboration with Frédéric Druot. Other notable examples are the Splayed Apartment blocks by Hans van der Heijden Architects on the outskirts of Rotterdam. This refurbishment considered the ageing population of the existing community and revitalised four modernist towers based on specific tenant needs, avoiding lengthy relocations and demolitions.

In Australia, Melbourne-based OFFICE architects have developed the retain, repair and reinvest (RRR) model and applied it to the since demolished Barak Beacon Estate.6 The model shows that a refurbishment and infill scheme could have achieved the government set housing target of 350 homes, with a 54% reduction in embodied energy and $86 million dollar saving in construction and relocation costs. The strategy maintained the existing community within the estate, reducing the time to house people. The RRR model provides a framework for an alternative strategy to the recently announced proposal to demolish all 44 social housing towers in Victoria.7

In NSW, refurbishment and infill programs have been undertaken before, with large-scale renovation of existing social housing stock coupled with new infill housing carried out in the late 1980s to 1990s.8 Refurbishment options have also been tabled for Waterloo Estate with the City of Sydney’s alternative masterplan retaining and refurbishing existing slab blocks and towers while maintaining the existing community through staged infill. A 2014 statewide report found that by 2029, more than half the state-owned social housing stock will be over 50 years old.9 Common typologies of Housing Commission –era buildings are brick walk-ups and towers which are of quality construction and built to last. The buildings are situated in open plan ground planes, providing ample opportunity for the infill of underutilised land while retaining and refurbishing existing homes.

When facing the larger forces that drive the housing market, architecture can feel like it lacks agency. Design solutions can foster better outcomes if we critically analyse the brief in search of better social, economic, and environmental outcomes. It is proven that refurbishment of social housing can achieve these outcomes, so it must be the first course of action when addressing existing stock.

A better way of providing housing is possible. Architects see the potential in the existing and no longer accept a brief that includes the demolition of social housing without a robust investigation into its adaptation and infill.

NOTES

1 Social Housing Waiting List Data, https://www.facs.nsw.gov.au/housing/help/applying-assistance/social-housing-waiting-list-data#social

2 https://7news.com.au/video/business/thousands-of-homes-across-sydney-sitting-vacant

3 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii

4 https://majorprojects.planningportal.nsw.gov.au/prweb/PRRestService

5 Jones, A Reviving the Block, https://www.architects.nsw.gov.au/download/BHTS/Alexander_Jones_Reviving_the_Block_BHTS_2019.pdf

6 https://office.org.au/api/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/OFFICE_RRR_Barak-Beacon_Report.pdf

8 https://s3.ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/dpe-files-production

9 Social Housing in NSW Discussion Paper, https://www.facs.nsw.gov.au

Alex Jones is a social and affordable housing practitioner at Less Stress Studio. The work of the studio focuses on social and affordable housing design and alternate methodologies to delivering better housing.