Museums have long served as cultural guardians, preserving and displaying collections of artworks, artifacts, and specimens that give insight into human history and the natural world. However, most museums prioritise the preservation of these objects, often enclosing them in glass vitrines and restricting direct physical interaction to protect fragile, light-sensitive, or irreplaceable items.

While this approach ensures the longevity of artifacts, it can also inadvertently exclude blind and low vision (BLV) audiences from fully engaging with exhibitions. For these individuals, the traditional visual-centric-museum experience becomes inaccessible, disenabling any meaningful cultural and historical connections.

The research project Museum of Touch (2023-) seeks to address this challenge by leveraging advancements in digital and tactile technologies to make museums inclusive for all. The project focuses on creating touch models – three-dimensional (3D) representations of museum objects – that enable BLV individuals to explore, understand, and connect with artifacts through tactile experiences. This approach embraces the multisensory nature of human perception, recognising that touch, sound, and even smell often play as significant a role as vision in understanding the world around us.

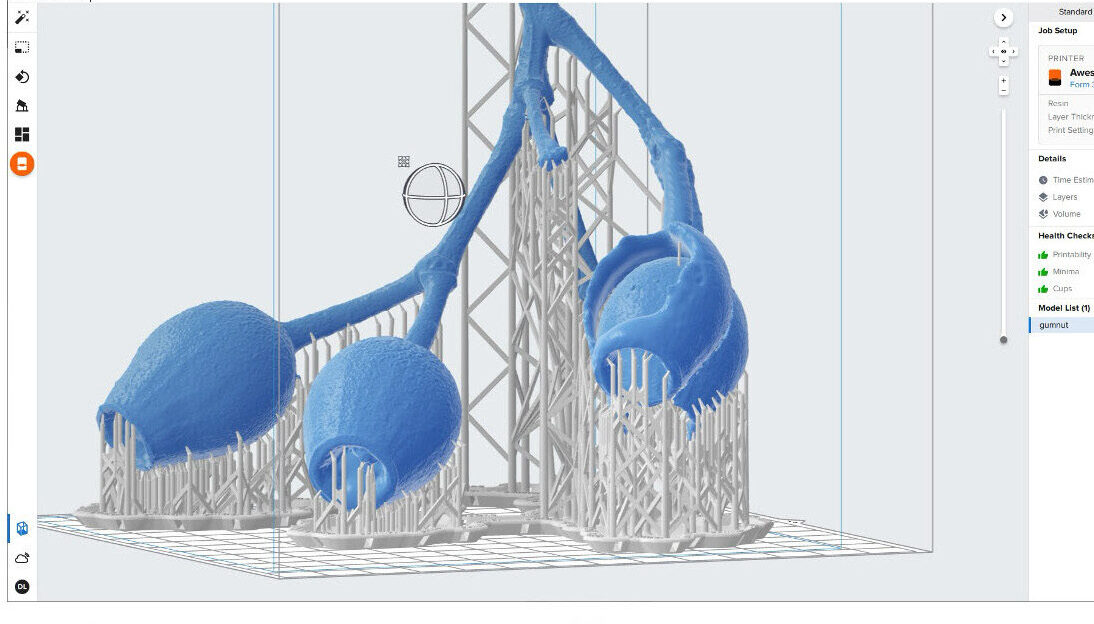

The project integrates emerging technologies, particularly digital scanning and 3D printing, to create tactile models of museum objects and specimen. Increasingly, museums are adopting digital scanning to create online repositories of 3D models, allowing audiences to explore collections virtually. By transforming these digital models into physical, touchable objects, the Museum of Touch bridges the gap between virtual access and real-world interaction.

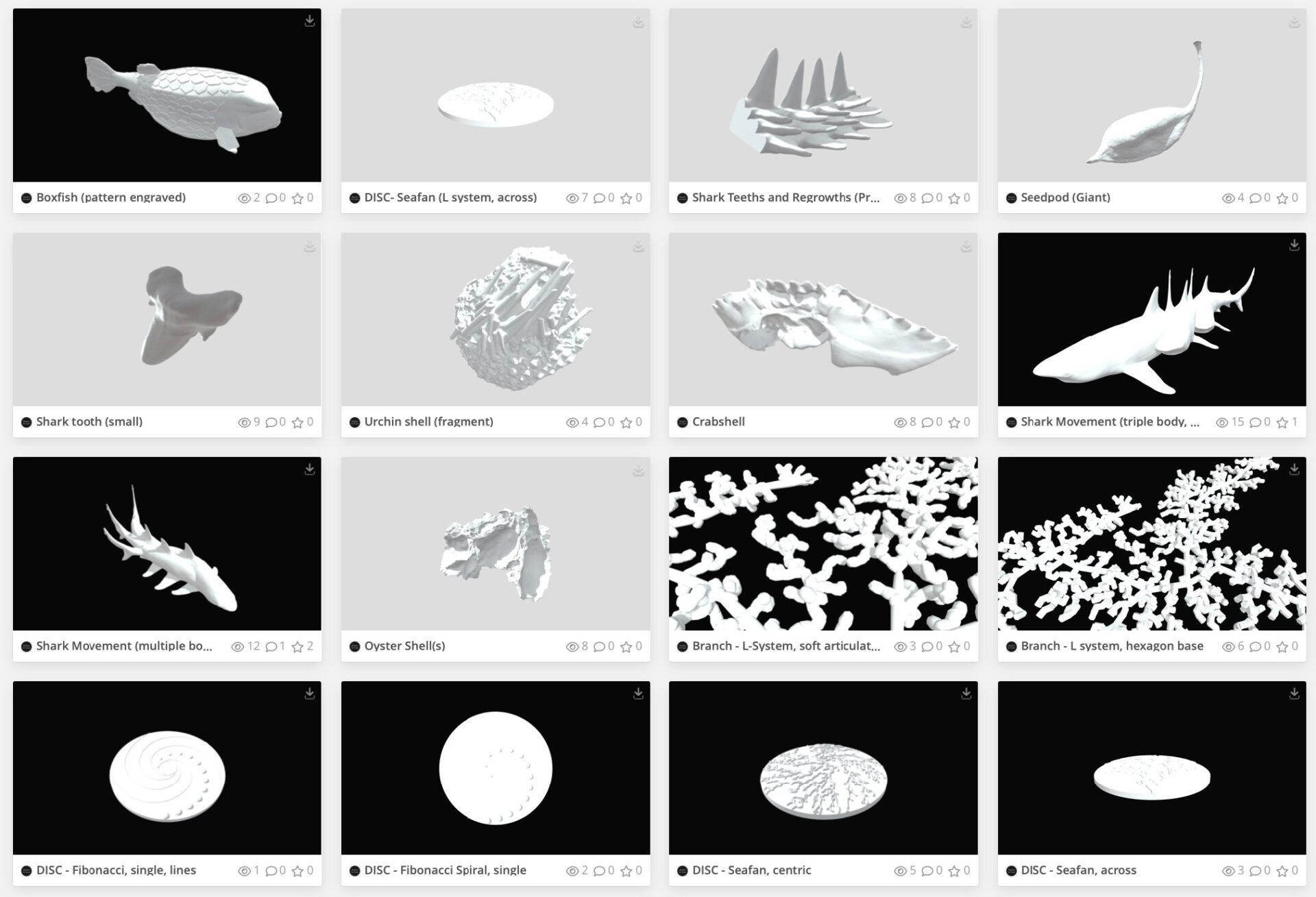

For BLV individuals, tactile information is a vital mode of processing spatial, structural, and narrative details. Unlike sighted individuals, who perceive an object holistically before focusing on specific details, BLV individuals explore objects piece by piece through touch, gradually assembling a comprehensive mental representation. High-quality tactile models provide these audiences with a deeper understanding of the forms, patterns, and stories embedded in museum artifacts. For example, tactile models can illustrate predator-prey dynamics through representations of sharks and teeth or explain mathematical growth patterns by comparing corals and trees.

Collaborative development and prototyping play a significant role for actively involved BLV people, both children and adults in the co-design and testing of tactile objects. This participatory approach ensures that the models are not only functional but also engaging and meaningful for their intended audiences.

Prototypes have included tactile maps, 3D-printed chairs with embedded information, and scaled-up models of intricate details that might otherwise go unnoticed.

Key strategies developed by the research group include:

– Developing workflows for 3D scanning and printing: These workflows can be adopted by other museums and educational institutions to create their own tactile models.

– Integrating multimodal elements: Combining 3D tactile models with audio guides enhances the storytelling experience, offering layered levels of explanation that cater to diverse audiences.

– Prototyping hyperartifacts: These multifunctional furniture pieces integrate visual, tactile, and Braille information, fostering collaboration between sighted and BLV individuals.

– Sharing open-access resources: By uploading models to platforms like Sketchfab, the project extends accessibility and knowledge dissemination globally,

– Designing educational toolkits: These kits include 3D models, activities, and exercises for use in museums and classrooms.

– Creating a user manual for BLV-friendly museum design: This includes advice on website accessibility, navigation strategies, and the implementationof touch stands.

Blending technology and design is another aspect of the project and one of its contributions: the development of hyperartifacts as tangible, multifunctional objects that integrate various sensory inputs.

The Museum of Touch adopts Universal Design, emphasising equitable, simple, and intuitive use for diverse audiences. By integrating tactile and visual narratives, the project not only makes museums accessible to BLV individuals but also enhances the overall visitor experience. This approach encourages empathy, understanding, and awareness of different sensory experiences, ultimately promoting more inclusive attitudes and behaviours.

The collaborative initiative involves partners from multiple institutions, including the University of Sydney’s School of Architecture, Design and Planning, Monash University, the Chau Chak Wing Museum, and international organisations such as the Institute for Blind and Partially Sighted (IBOS) in Denmark. Funding from the Alastair Swayn Foundation International Grant 2023 has supported the project, ensuring that its outputs remain free and open-source. Resources, including 3D models and a comprehensive report, are available online, providing museums and educators worldwide with the tools to adopt and adapt these strategies. By making these resources publicly accessible, the Museum of Touch aims to inspire broader adoption of tactile technologies and inclusive design practices across cultural institutions.

Museums have a unique opportunity to reimagine accessibility, not just as a compliance measure but as a chance to enrich the visitor experience for everyone. By embracing the potential of touch and tactile narratives, museums can break down barriers, foster inclusivity, and create spaces where all individuals – regardless of sensory abilities – can engage with and learn from the artifacts of our shared history. The Museum of Touch demonstrates how technology can drive this transformation, offering a blueprint for museums to become more inclusive, engaging, and exciting for all audiences. Through collaboration, innovation, and a commitment to accessibility, the project not only opens doors for BLV individuals but also sets a new standard for the future of museum design.

Dagmar Reinhardt is an architect, researcher and associate professor at the School of Architecture, Design and Planning, the University of Sydney. As a practising architect, her built works, competitions and installations are widely published and have received numerous recognitions and awards. Reinhardt’s research focuses on human-centric design at the nexus of acoustics, robotics and accessibility. Reinhardt’s funded research projects explore museum accessibility and the ARC DP24 research Accessible Playgrounds for Blind and Low Vision Children and their Parents/Carers.