Jaghori + architect Belqis Youssofzay

I’m Rehila (pronounced: Ra-he-la); I was born in Afghanistan, in a small town in the district of Jaghori in the province of Ghanzi. Due to conflict and unrest brought on by the Taliban, my family migrated to Melbourne, Australia in 2005. In some ways, it was the experience of a radically different place that drew me to the study of architecture; a sense of curiosity about why we construct environments the way we do and how the built environment can support diverse ways of living.

Introducing my Jaghori

My family home in Jaghori, Ghazni, is now home to my great aunt. A two-storey dwelling, it rests on the side of a hill, a topography which defines two villages. Like many nearby dwellings, it is assembled of local materials, clay, and straw. Immediately in front of the house, a narrow stream flows from a natural spring, the water source for the whole village and their crops. Water distribution is visible on the ground surface, a network of narrow streams, together with a watering schedule that ensures equitable sharing.

The house is in immediate proximity to the village mosque, used for prayer, and in addition, as a classroom, collective ceremonies and guest accommodation. I left my home at the age of four, and before returning in 2015 my memory of the place had faded – but a few visceral recollections remain. Clear memories of a small room at ground level held the details of its earthen floor heated by channels of warm air from a dug-out kiln. My four siblings and I were born on this floor. The only frame for natural light within this intimate room was a singular small window. The wooden balustrades, not polished or neatly cut, but made from branches of nearby trees are retained in my memory through their grooves and texture, the shape and touch.

This house, this room, and the spot under the small window capture dwellings as primordial support for human life –a recollection of the magical and intelligent network of local streams, the ability to build from materials of the land, and the proximity of a generous public room. These architectural lessons inform my work and invigorate my approach to contemporary architecture. When visiting this home, I think of the sheer resilience of my mother and father to pack what little they could and leave their home.

Introducing architect Belqis Youssofzay

When the Taliban took over Afghanistan in 2021, many of the Afghan diaspora were concerned about the safety of loved ones that still lived there, and the broader cultural erasure that could follow – as it had occurred two decades earlier. It was at this time that I came across architect Belqis Youssofzay of the Sydney-based practice Youssofzay and Hart. She was working alongside a group of Afghan-Australian artists, poets and lawyers to advocate for the preservation and awareness of Afghan culture. Youssofzay was born in Afghanistan and moved to Australia at a young age. I felt a strong sense of affinity and admiration for her as an Afghan Australian, but also for her social and environmental advocacy through the practice of architecture.

By introducing Youssofzay here, I want to draw attention to the significance of Afghan role models here in Australia. My sense of cultural and ethical alignment with Youssofzay’s work enables me to imagine a positive and powerful engagement in the professional world. Such role models are critical to the making of a rich and diverse architecture profession.

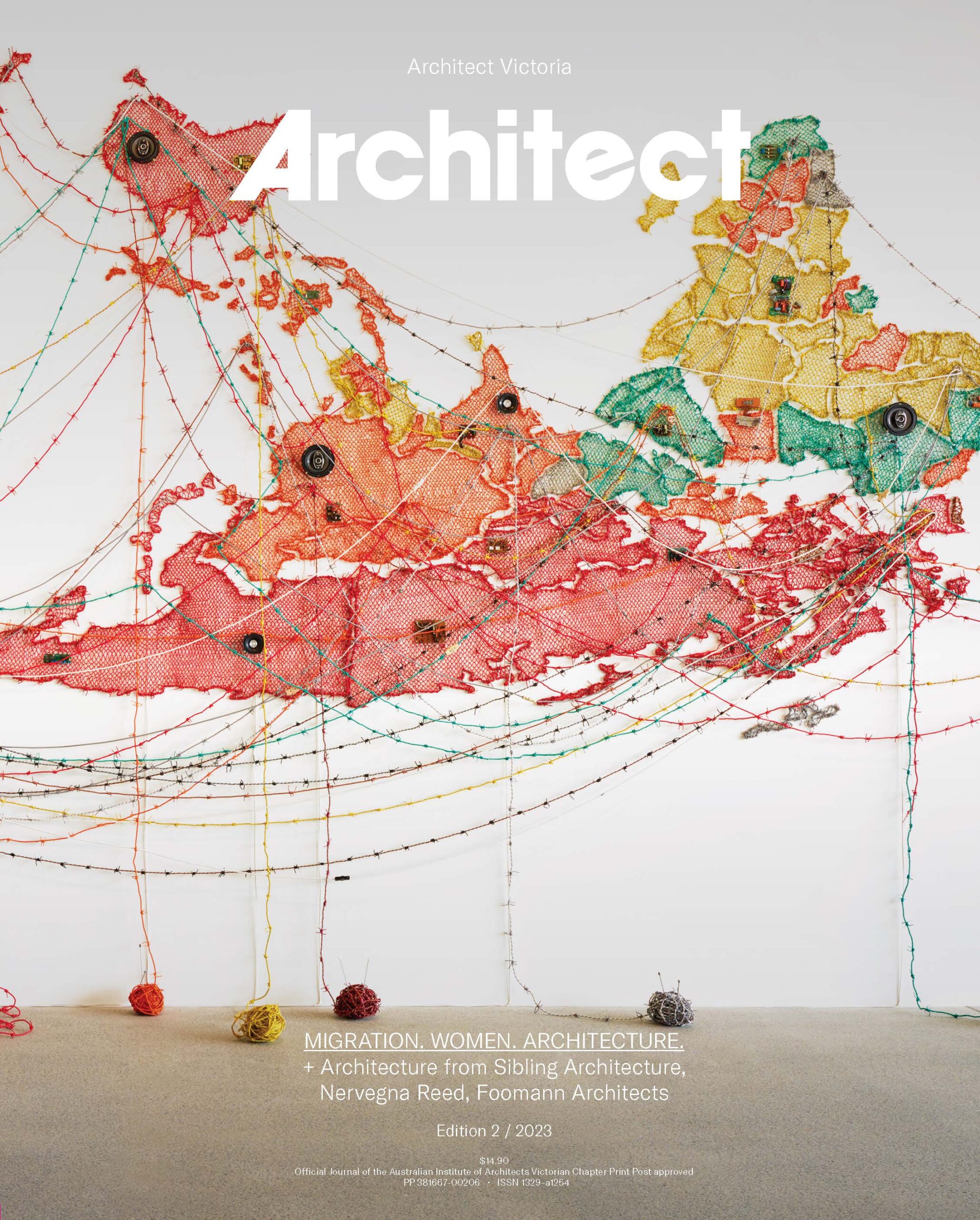

The diversity of Youssofzay and Hart’s work and their commissions is impressive – there are small exhibition designs and large-scale collaborative public commissions. Their recent temporary installation, No Show at Sydney’s Carriageworks (2021) speaks to a number of priorities within and across their work. No Show comprises a temporary scaffold for artworks, and has a gentle formal integrity as well as an ability to recede and host work by others. The project evokes a delicate response to the setting, elegant material detailing with respect for sustainable material choices and lifecycle principles. It carefully mediates the human scale and larger shared environment – at once, contemporary, sustainable and sensitive.

Rehila Hydari is a student of architecture at Monash University.