Hargeisa + architect Rashid Ali

Words by Mulki Suleyman

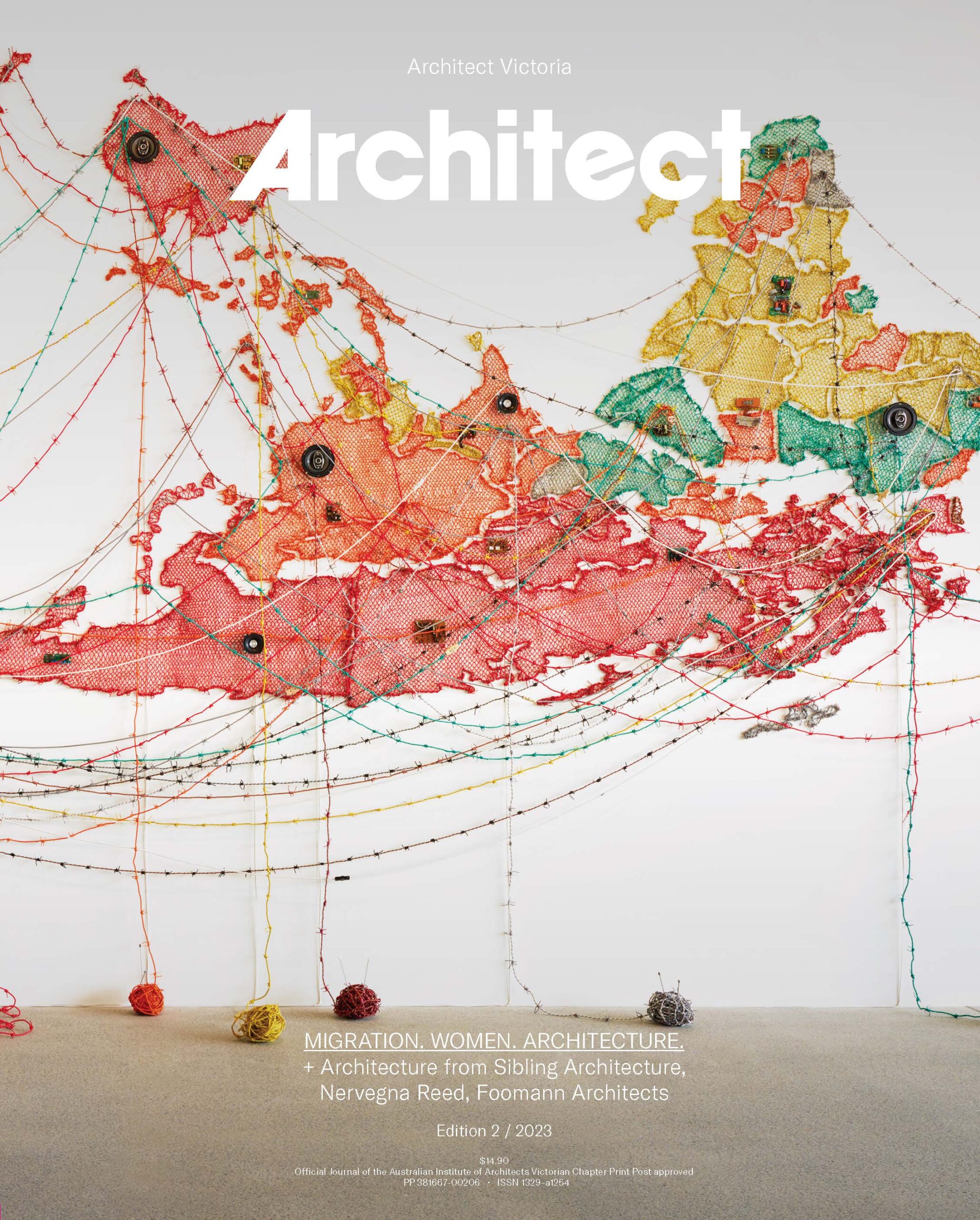

I consider myself a true nomad. My family fled Somalia in the 1990s as refugees seeking new beginnings for their children and settled in Nairobi for almost eight years while they sought asylum overseas. I grew up around grandparents and aunties who designed their own patterns and embroidered on fabrics. I recently received one from my aunt. Precision and patience, this was art! The lesson was passed on to me. I consider myself lucky to have come from a matriarchal society, I have been around strong independent women who crafted their way in life. I had no point of reference and neither did my family to the study of architecture or art, so it was safe to study medicine as it was common practice. Then I took a leap of faith and transferred to Master of Architecture and Bachelor of Construction Management at Deakin University.

Introducing my Hargeisa

I have little memory of my childhood in Hargeisa, Somalia. One of my key childhood memories is when we lived in Nairobi, Kenya (1990-1998) in a large and enclosed central courtyard style architecture complex. The entire complex was about 60 metres by 25 metres made of masonry and was secure with only two entries to the complex. I came to realise later that this courtyard typology was prevalent at the border of Somalia and Kenya. All doors from the private dwellings faced the courtyard; and the courtyard was only partially covered by a verandah that ran around this private/communal edge.

In this courtyard, we lived with our cousins, aunties, uncles, grandparents, and other close family friends. Each family had one or two rooms. All cooking was done outside the private rooms in the courtyard and there was a common/shared toilet and shower facility for all. The children played in one part of the courtyard away from where families cooked or where the washing was hung. Families often cooked together and shared meals – there was such a strong sense of community inside the courtyard walls.

We didn’t always have electricity/light, we relied on candles and paraffin lamps. These are days gone. I miss this type of gathering when sometimes the elders tell stories about things they once used to do. We didn’t grow up with television or toys for entertainment and often made our own toys –windmills out of plastic bottles, cars out of wire and houses out of cardboard. My upbringing allowed me to think outside the box, to engineer and design different elements. This was driven by necessity, and I look back with gratitude.

Introducing architect Rashid Ali

I have recently come across the work of Rashid Ali, a London-based architect who has ancestral roots in Hargeisa. Knowing the struggles Somalia has had over the last three decades, I am inspired by architects like Rashid Ali who are willing to go back and rebuild Somalia.

His recent work resonates with my own thesis on post-war reconstruction (Deakin, 2008). The simplicity of the Pink Pavilion considers a delicate and overlooked need within the urban hustle and bustle of a city like Hargeisa. The pavilion provides shelter in a hot and dry arid environment. In a busy town like Hargeisa, Ali has created a modest and tranquil space, a setting for old time storytelling – as if under an acacia tree; a place for people to gather and exchange information or stop and pause on their journey to work or home to their families. It is both a place to rest – a breathing space in the city; and a space to gain information and interact with others.

The design layout is reflective of the courtyard housing complex in Nairobi, and is also partially covered creating a verandah, allowing natural ventilation. It is accessible to everyone creating a communal gathering space for people to share stories, create embroidery, resolve conflict or merely relax and enjoy the surroundings. Ali’s design is rooted in the traditional Somali lifestyle, one of inclusivity, where the spoken word and shared understanding occur in gatherings.

Most modern pavilions are often temporary with a transient purpose; this is a permanent structure and is thus significant as a reminder of Somali historic tradition and stories once told under the Acacia tree rooted in the red earth.

Mulki Suleyman is a principal project manager at Homes Victoria.