Australia’s First Peoples live a relational cultural framework binding us to the natural world and each other. Lived experience is not an abstract philosophy, shaping communities and world views. Deep, enduring connection to Country – nature and humanity existing in mutual reciprocity – requires individuals to be responsible for the wellbeing of Grandmother Earth and others in our roles as Custodians. Australia continues its truth-telling journey and reconciliation, Indigenous understanding’s potential to reshape broader non-Indigenous Australian stories, creating more inclusive futures, vernacular in character and ecologically self-perpetuating.

AN AGILE CHANGING LANDSCAPE

Indigenous Australians display agility in adapting to shifting environmental landscapes, enduring ice ages, navigating rising and falling sea levels, fires, floods, and our old people continuously adjust their ways of living, resilience stemming from an all-encompassing relationship with the natural world, a relationship deep and intertwined feeling as if nature itself has sung us into belonging.

Belonging is not land ownership in the Western sense, but an existential and philosophical worldview positioning human beings within nature, not above it. To belong to Country recognises human life as one thread in a vast ecological matrix, where individuals are responsible for the wellbeing of others, human and non-human, where ideas of personal assets or property are incongruent with complex systems placing the collective and natural world at existence’s centre.

REIMAGINING DESIGN THROUGH A COUNTRY-CENTRIC LENS

Incorporating this worldview into contemporary design, particularly architecture, a significant thinking shift is required. Rather than liberating individuals, often the case in Western design thinking, architects and designers must prioritise a Country-centric understanding of place, abandoning notions of buildings and structures as isolated entities, seeing them as integral parts of an interconnected social ecology.

Traditionally, Elders spent years with young people, teaching them to read landscape, interpret lores, and understand their responsibilities within this system. Ways of learning not confined to specific time or place but embedded in every aspect of traditional life. In modern contexts, where knowledge has been fragmented or lost to colonisation, many Indigenous communities are working to piece together old ways.

THE ROLE OF TECHNOLOGY IN COUNTRY-CENTRIC DESIGN

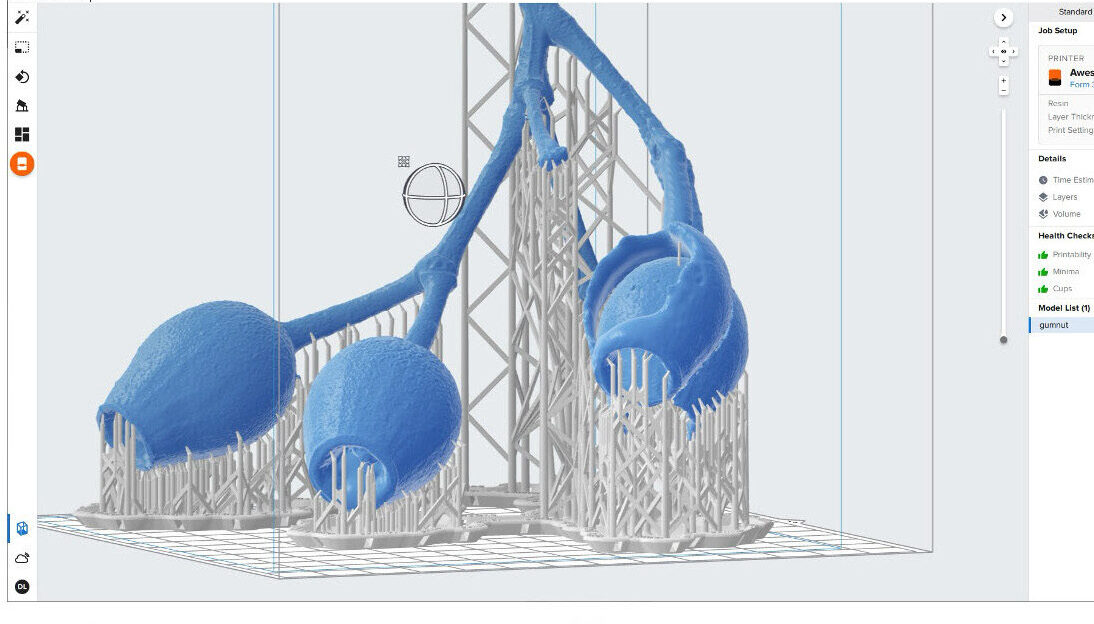

Technology plays an important role in helping architects and designers work from Country-centric perspectives. In the absence of walking Country, we can reimagine this songline journey through sophisticated mapping systems like GIS. Replicating the songline journey can be achieved by replicating a digital twin of the topography. Undulations of the landscape comes to life with vectorised models. These programs allow us to switch off roads and infrastructure and see through into the natural landscape casting alternate priorities to view the landscape through. One particular mapping QGIS allows us to visualise the mountains, valleys, creeks, rivers and lakes. Through this, we are able to recreate the essence of the water journey and migratory patterns.

Sitting with Uncle on the NSW South Coast, he spoke of the songline from Eden up into the Snowy Mountains and how his people would regularly walk this Country. An air of mystery filled the room. How did they know where they were going? What did they eat and why did they take on such a daunting journey.

Looking through geo-referenced Aboriginal site archives, we overlayed this with typography and could quickly visualise the ridgelines that provided walking tracks, valleys where old people found game, water and tools. Technology allowed us to join dots along numerous ridgelines traversing the terrain, that may have been markers, carved scar trees and directional navigation markers.

Topography aside, we can enrich education and understanding by using Indigenous language – made accessible through plug-ins incorporated into computer aided drawing programs to facilitate use of traditional words within our cultural mapping.

From a broader view, we capture the interconnected quality of Yuin journey through Country, reframing worked site to be understood as part of The Bundian Way – a songline path which spans from coastal Twofold Bay in Eden inland to Mount Kosciuszko Snowy Mountains – a meeting place which forms part of a cyclical passage of kinship and seasonal travel.

TECHNOLOGY AND COUNTRY: A NEW HARMONY

For some Indigenous people, digital technology’s rise is seen as a threat to the relationship with nature, a force pulling individuals away from the physical world and into the digital realm. But some see technology not as an antagonist but as another tool that, like so many others before it, can be adapted and integrated into Indigenous ways of expression. The digital twin becomes a meeting place revealing old stories and ways of living, validating what Elders say, cementing their stories and facilitating clear ways to represent the story of place.

For Indigenous architects and designers, technology offers new ways to express their deep connection to Country. For non-Indigenous architects and designers, and for clients, project stakeholders and the general public, allowing First Nations knowledge to translate with clarity and impact.

Allowing for broader and more precise understanding of our natural world and social ecology, topographic mapping captures water flow through landscapes, showing small, ephemeral creeks connecting larger rivers and brackish flood plains flowing to sea. Digital tools help architects visualise and communicate natural systems and design buildings responding to, rather than dominating, surroundings.

SONGLINES AND MAPPING THE LAND

Technology assists design by reimagining ancient songlines and pathways First Peoples have followed for tens of thousands of years. Songlines are not just physical, but cultural maps carrying knowledge of where to find food and water, ceremonial sites, where one language group’s land ends and another’s begins. Overlaying digital maps with cultural artefacts and topographical data, architects can reconstruct ancient routes and understand landscape once again, enabling an understanding the specific relationship that our site has to a broader network.

Carved scar trees may signal travellers have entered another language group’s territory and must seek entry permission. Landscape becomes a living document, guiding human behaviour and ensuring the natural world is respected. Digital technology, when used thoughtfully, brings these stories to life, creating bridges between old ways and a misinformed modern world.

A BROADER PERSPECTIVE: ZOOMING OUT TO SEE THE WHOLE

In designing from Country-centric perspectives, first zoom out – at national or global scales. Reframing site meaning within broader ecological and cultural contexts, not just the immediate environment, architects can consider a site’s fit into the larger system, something Indigenous people always understood, as they have seen themselves as part of an interconnected songline, taking responsibility for everything beyond the self-biosphere.

When rivers are sick, so are people who rely on them. When land flourishes, so too does the community. Understanding mutual dependence brings lightness and weightlessness to individuals, grounding us in larger stories not just about our survival but entire ecosystem’s wellbeing. Reminders are beyond self-pursuits and have responsibilities to care for that system. Designing from a macro understanding, we must orient thinking to immediate sites and become part of a larger relational context.

CONCLUSION: RELATIONAL FUTURE

Ultimately, Australia’s First Peoples offer powerful alternatives to individualistic, human-centric worldviews dominating contemporary design approaches. Deep connections to Country remind us of our part in the natural world. Technology evolves, growing opportunity to embrace it, not capturing spatial boundaries, but reconnecting blurred lines between nature and humanity though Indigenous spatial intelligence. By adopting Country-centric approaches to design and architecture, we create spaces honouring our social ecological systems, fostering more sustainable, inclusive, and relational futures, creating belonging and identity

Craig Kerslake RAIA is a Wiradjuri architect who draws upon his cultural heritage community of Aboriginal people’s knowledge referred to as Country. He is managing director at Nguluway DesignInc driving innovation in forming spatial design and architectural form with a unique expression. His cultural overlays draw design thinking to the unexpected and provides positive outcomes focused on Aboriginal centred qualities, spatial unity and scales of social engagement.