Capturing and communicating social impact

To say that social impact is moving up the agenda of responsible UK built-environment professionals would be a bit of an understatement. And this is despite the fact that, until recently, it has been such a difficult quality to define and measure.

Given that chartered status with the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) requires a practice to “consistently promote and protect the public interest and social purpose,”1 positive social impact should be written into the DNA of every architecture practice – from the way it works with its staff, to the way it designs buildings, the way these buildings sit within their surroundings, and of course the lifestyles made possible by the buildings and places it designs.

If only this was the case. As I argue in my book Why Architects Matter,2 the rise and rise of the social impact agenda is an opportunity for architects – but it requires a change of mindset about the ways in which practices evidence and communicate their value.

One obstacle lies in the lack of agreement on what constitutes “good” or “quality.” I argue that “design value” aligns with the commonly used “triple bottom line” of sustainability – social, environmental and economic value – with the addition of cultural value, which must be recognised as a vital ingredient in sustainable transformation. The Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015 is a ground-breaking piece of legislation in this space. Australian legislation regarding intangible heritage, including the Burra Charter, has also played an important role in bringing about this transformation.

Social impact comes in a variety of guises, which are not yet all aligned. It cuts across the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals in a way that makes it difficult to pin down. It can be used as a proxy for “wellbeing,” “quality of life,” “resilience” or “social value.” Meaningless to non-experts, the term “social value” has been enshrined in the UK’s Public Services (Social Value) Act 2012, which requires bodies that are using public money to demonstrate social value. This principle is gaining prominence in Australia.

After the implementation of the Social Value Act in the UK, construction companies were quick to develop systems for quantifying social value – for example, numbers of ex-offenders employed on site. However, their focus has been on the construction phase, rather than on the social value delivered to people after completion, or indeed the social value of any engagement strategy at the outset. Our aim with the publication of the RIBA Social Value Toolkit for Architecture3 was to demonstrate that well-designed buildings deliver on social value. It didn’t take long for the social value of buildings in use to be firmly on the agenda, embedded into experimental digital platforms such as the Construction Innovation Hub Value Toolkit,4 which was developed to facilitate values- or outcomes-based procurement.

It has to be said that industry in the UK has been slow to catch on to these changes, perhaps because of a lack of incentivisation from government. But some powerful property developers, such as Grosvenor, are being quite forensic in capturing the social value of their supply chains. There is also an increasing number of Certified B Corp architecture practices – for example, Stride Treglown – who are trying to put social sustainability front and centre.

Environmental, social and governance pillars (ESG) ought to be another driver for social impact. If developers can demonstrate ESG, they are likely to be charged reduced interest rates by funders, which can make all the difference to overall viability. Like social value, ESG is also highly contested when it comes to measurement. I’ve interviewed many developers and they tell me that funders are becoming increasingly sceptical about the manifold and flimsy ways in which developers are expressing their ESG. One way to solve this issue would be to align ESG to the triple bottom line, creating a golden thread of value across the project delivery system.

Building procurement remains a problem, particularly for architects who can’t afford to employ social value consultants to help with complex paperwork. One irony is that some of the practices demonstrating the highest level of social value are those least likely to be able to express their social value well. I’ve been impressed to see some particularly responsible and creative funders – RailPen, for example – holding the hand of bidding teams to help them communicate their social value in ways that align with the funder’s own values. This type of assistance develops capacity within the system.

When you are bidding for a job, a tiny increase in social value marking can make all the difference. Some practices have reported that they’ve won jobs based on their use of the Social Value Toolkit to improve their social value statements. This surprises me, as we still have so far to go to ensure that the questions asked by procurement teams align to good work in this area. Typically, “social value” is a small increment of the overall mark allocated to bidding practices, with the very elusive “quality” attracting a far higher weighting. I’d like to see the marks divided into thirds (or quarters, if culture is to be included), giving 33 per-cent to each of social, environmental and economic value.

Over the past few years, we’ve seen local authorities – including the City of Manchester, for example – beginning to use social return on investment (SROI) to monetise social impacts. But I sense a turning of the tide in this area, with growing cynicism around the use of financial proxies. In the Social Value Toolkit, we set out a method for monetising social value, but only to make it a less scary process for practices.

I believe that monetisation will be disrupted by the development of intelligent maps that chart change in real time. Together with research colleagues in the UK and Australia, I’ve been working on a series of research projects that explore the mapping of social value. There are evolving methodologies for mapping environment and economic value, with work to be done on social value. The ultimate aim is to have a planning system based on value expressed spatially in real time. Value can then be coded into local plans, so that stakeholders know that “x” social value is required here, or “y” environmental value is required there.5 Developers will have to demonstrate how their proposals will contribute to that value; the only effective way to do this will be to undertake post-occupancy evaluation on projects delivered in the past.

UK policymakers are alive to the benefits of a more automated planning system (with vital human checks), but are failing to roll it out in the UK because local authority planning departments have been cut to the bone in terms of funding. Our Public Map Platform initiative6 is developing a pilot map of the Isle of Anglesey in North Wales using approximately 2,000 layers of data enshrined in Data Map Wales as well as community-made data to create a map to chart progress towards the Well-being of Future Generations Act wellbeing outcomes. That we need intelligent maps to provide holistic spatial data about places is becoming widely recognised – for example, through the work of the UK Geospatial Commission and the Digital Task Force for Planning.

AI and deep data are making the capture of intangible social impacts much easier. I am working with researchers at the London-based architecture practice Pollard Thomas Edwards to create a Happy Homes Toolkit. Conceived as a BIM-based tool, it measures and predicts the social value of housing by identifying social value “archetypes” in housing and the complex interactions between them.7

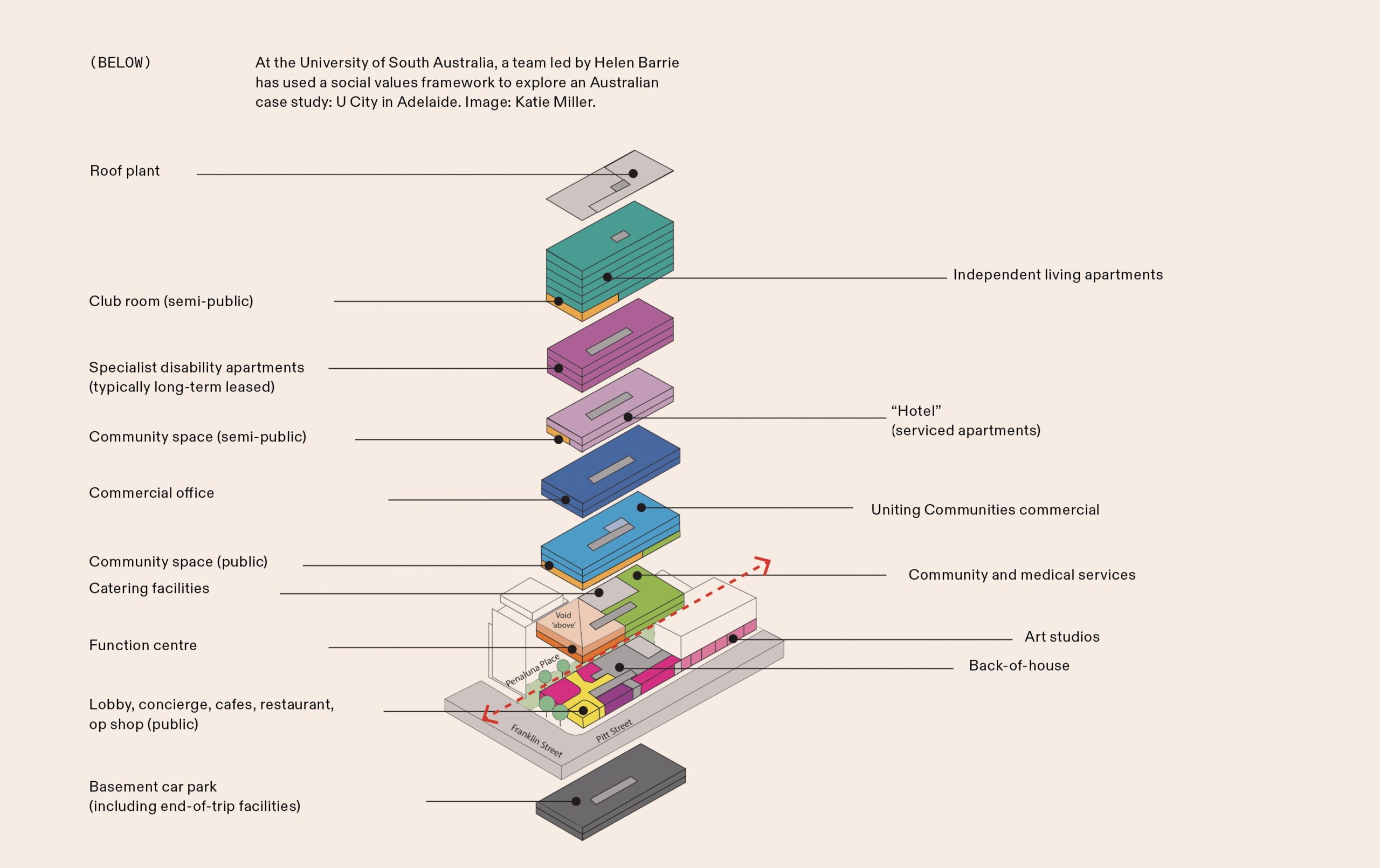

In the Australian context, Helen Barrie is leading the charge in social value research. Her team at the University of South Australia has been studying the social value of U City, a mixed-use highrise building in Adelaide. The work “supports improved design/project briefings and promotes new market opportunities for innovative, regenerative vertical urban villages that incorporate flexible, engaging public spaces for community to thrive.”8

New tools to capture social impact are arriving on the scene thick and fast. Architects ignore them at their peril.

Notes

1 Royal Institute of British Architects, RIBA Code of Practice, “Principle 1: Integrity,” 1 May 2019, available at architecture.com/knowledge-and-resources/resources-landing-page/code-of-practice-for-chartered-practices

2 Flora Samuel, Why Architects Matter: Evidencing and Communicating the Value of Architects (Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2018)

3 Royal Institute of British Architects and University of Reading, Social Value Toolkit for Architecture, 2020, available at architecture.com/knowledge-and-resources/resources-landing-page/social-value-toolkit-for-architecture

4 Construction Innovation Hub, Value Toolkit; constructioninnovationhub.org.uk/our-projects-and-impact/value-toolkit

5 I set out this vision in my book Housing for Hope and Wellbeing (Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2023)

6 Public Map Platform is a two-year research initiative led by Cambridge University. See publicmap.org/en.

7 See happyhomestoolkit.co.uk

8 Helen Barrie et al., “The social value of public spaces in mixed-use high-rise buildings,” Buildings and Cities, vol. 4, no. 1, 669–89; doi.org/10.5334/bc.339

Flora Samuel is a British architect, author and academic. She is the Professor of Architecture (1970) and head of the department of architecture at Cambridge University, UK.

Published online:

10 Jul 2024

Source:

Generating social value:

From procurement to delivery and beyond

Jul / Aug

2024