Belonging to Country – yindyamarra winhanganha

Words by Craig Kerslake

During the time when people thought they could roam here and there, going wherever they pleased, the river seemed to always get in their way. Try as they did to cross or go around, the river would always be there. They seemed lost, flitting this way and that, sometimes going around in circles. They would yell at the river in anger.

When some people sung with yindyamarra, softly and respectfully, to the river about this she started to speak with them. She invited them to come into the water and close their eyes to dream. They started to float, they were carried downstream, across the landscapes, through the earth and up into the trees. Up into the branches, twigs and leaves. Then into sky camp until finally the clouds brought them back to the land.

When they returned to Country the river flowed in their bodies. In their veins, their eyes and out through their skin. They had become the river, and she had become them. They belonged to each other now. The people were together too and could now speak with her and she always showed them the way.

Within our practice, we aim to amplify the voice of Australia’s First Peoples, extending into the fabric of the built environment to inform architectural expression in a vibrant and engaging way. It is through the social construction of our environments – the spaces we live and work in – that critical relationships are defined; relationships between people and with the natural world.

Influenced by many Aboriginal Elders and respected thinkers, my world view is that human relationships with the natural world are in fractious disharmony and the implications of our ways are profoundly untenable.1 The pursuit of liberalism and individual freedom has separated people from each other and from the natural world in which we all live.

With the human focus being reduced to work and the ownership of property, our collective identity has largely been lost. Inaction is incentivised to result in complacency and tolerance to the problems around us. Our sociopolitical system is ambiguous and bland, with obscured propositions that fail to connect us with place and disallows us from belonging to place. Yet, it is strong collective purpose that many of us, including me, seek to belong to and be a part of. Commitment to meaningful causes beyond the self that allow us to understand ourselves as being part of an integrated system imbued with spirited generosity for others.

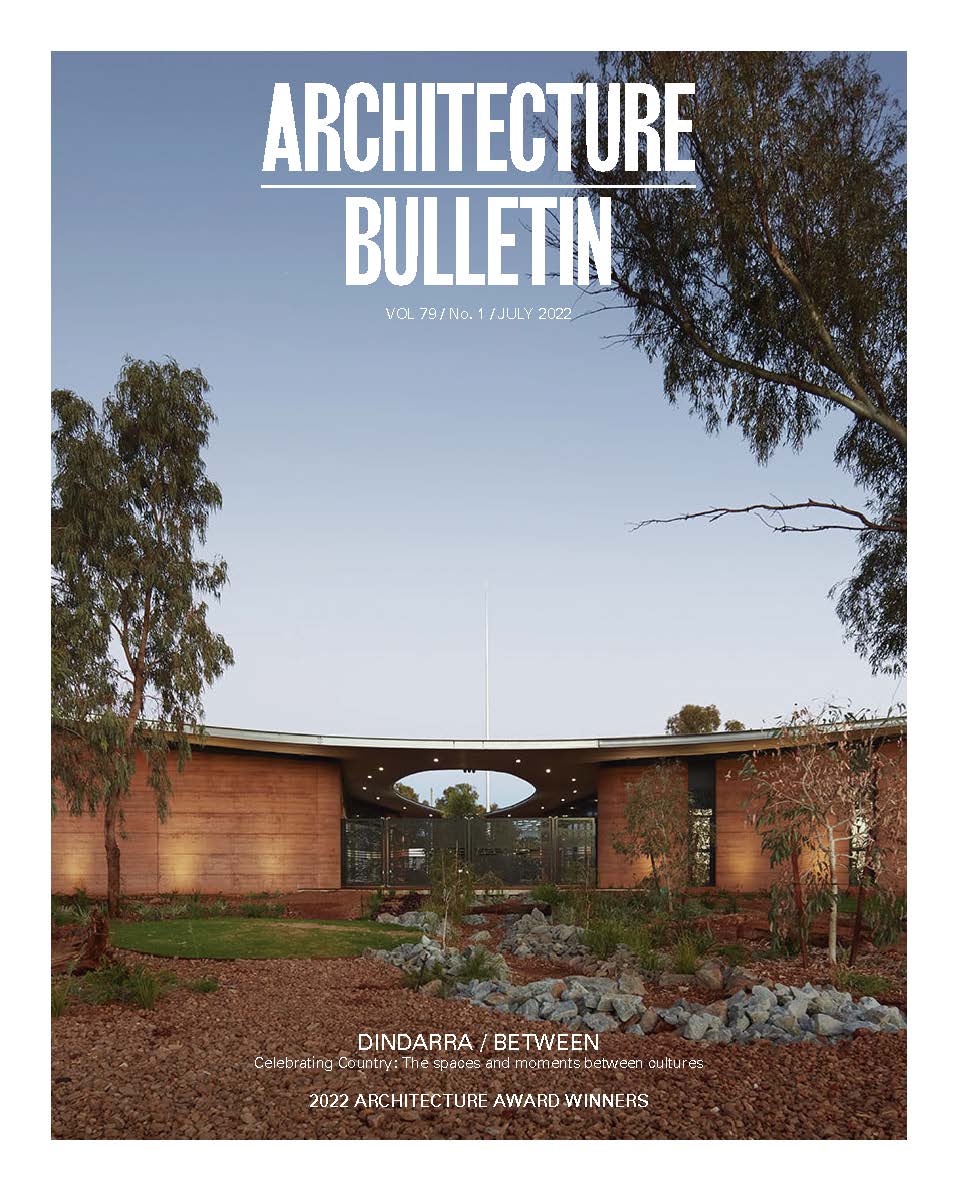

Architecture is unique. It connects environmental, economic, social and political networks. It is intermeshed with market forces, policies, regulations and communities. And while I believe that the sociopolitical system that architecture resides within is fundamentally dysfunctional, I propose that in Australia, collectively, architectural thinking has the power to challenge the footholds of liberal capitalism and to re-frame the priority of the individual. Often marshalled by time and cost, project managed to short term political moments, our architecture can become a transactional expression of narrow and at times confused parameter-based aspirations. But what would our built environment look like if informed by a culture-based social structure steeped in tradition and timeless qualities of Country?

YINDYAMARRA WINHANGANHA AS ARCHITECTURAL MANIFESTO

“The wisdom of respectfully knowing how to live well in a world worth living in”2

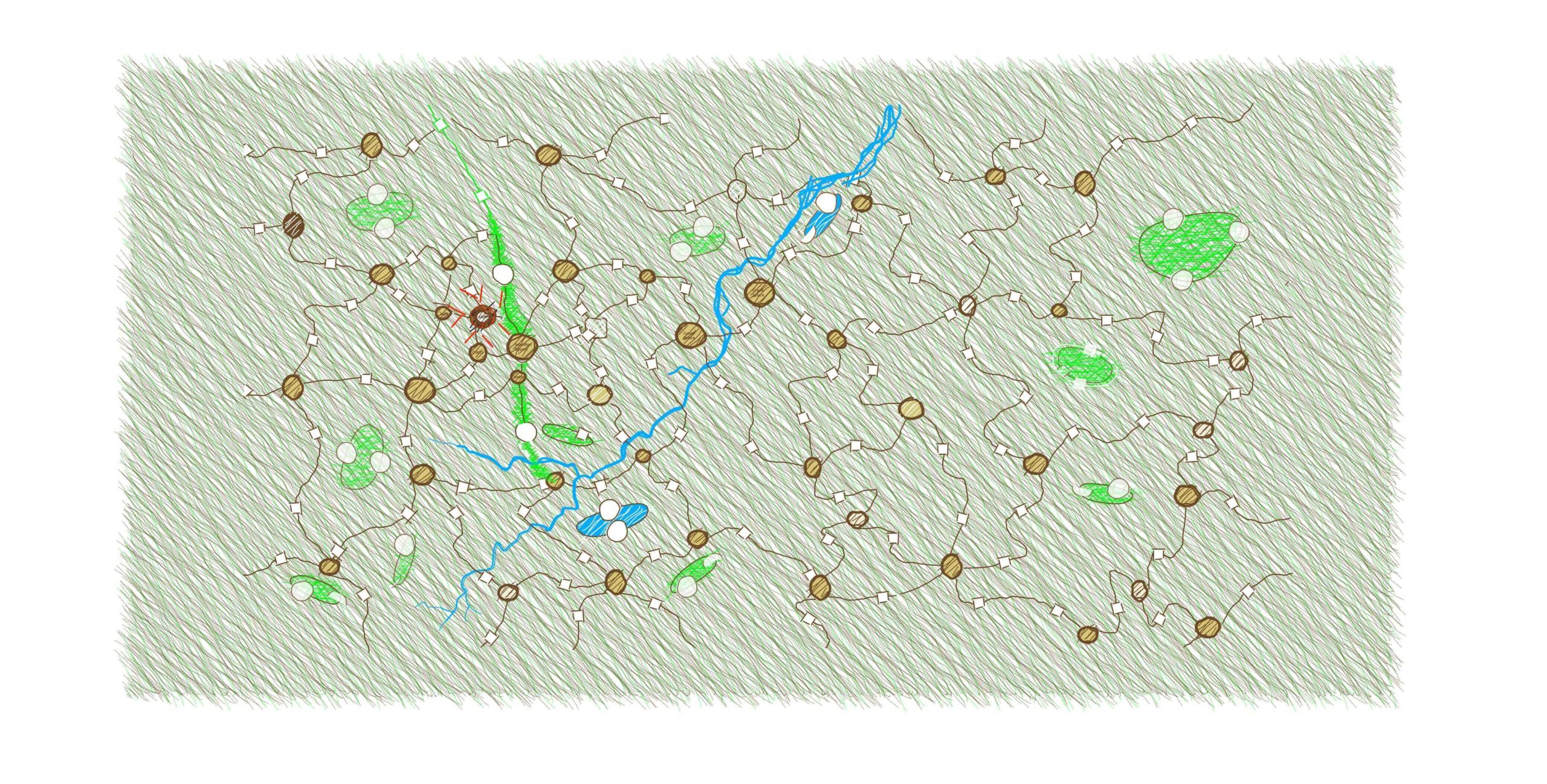

Indigenous thinking around the world contrasts liberal individualist sociopolitical thinking. The Wiradjuri perspective, like many Indigenous social systems, is centred on relationships and connections within an enduring continuum of mutual responsibility. Evolved over thousands of years, the philosophical understanding of the individual for Wiradjuri significantly reduces the prioritisation of the self. Instead, the individual is bound by social contract, required to contribute to and be responsible for the greater good of the collective. Surprising to many, this also embraces and includes of the natural world to which we belong.

The social character of focusing on oneself is typically understood as a momentary fall from social grace. In contrast, individuals must fit into the relational context of other people and then within the natural world with all understood as family. Elders and Indigenous thinkers3 tell me that there is no binary separation between nature and human cultures. We are one and the same. This thinking is referred to as Belonging to Country. I have been taught to understand Country as everything within my conscious world, trees, rivers, sky, oceans, animals and people. With human bonds strongly entwined with family kinship and our personal connections, to belong to, and identify with specific landscapes and nature. For the architectural context, yindyamarra winhanganha forms the basis of many propositions as part of and an extension of my cultural practices. As a result, I find an endless array of compelling design possibilities firmly anchored within an authentic Australian vernacular.

TO DESIGN FROM COUNTRY, BUILT FORM MUST BELONG TO COUNTRY

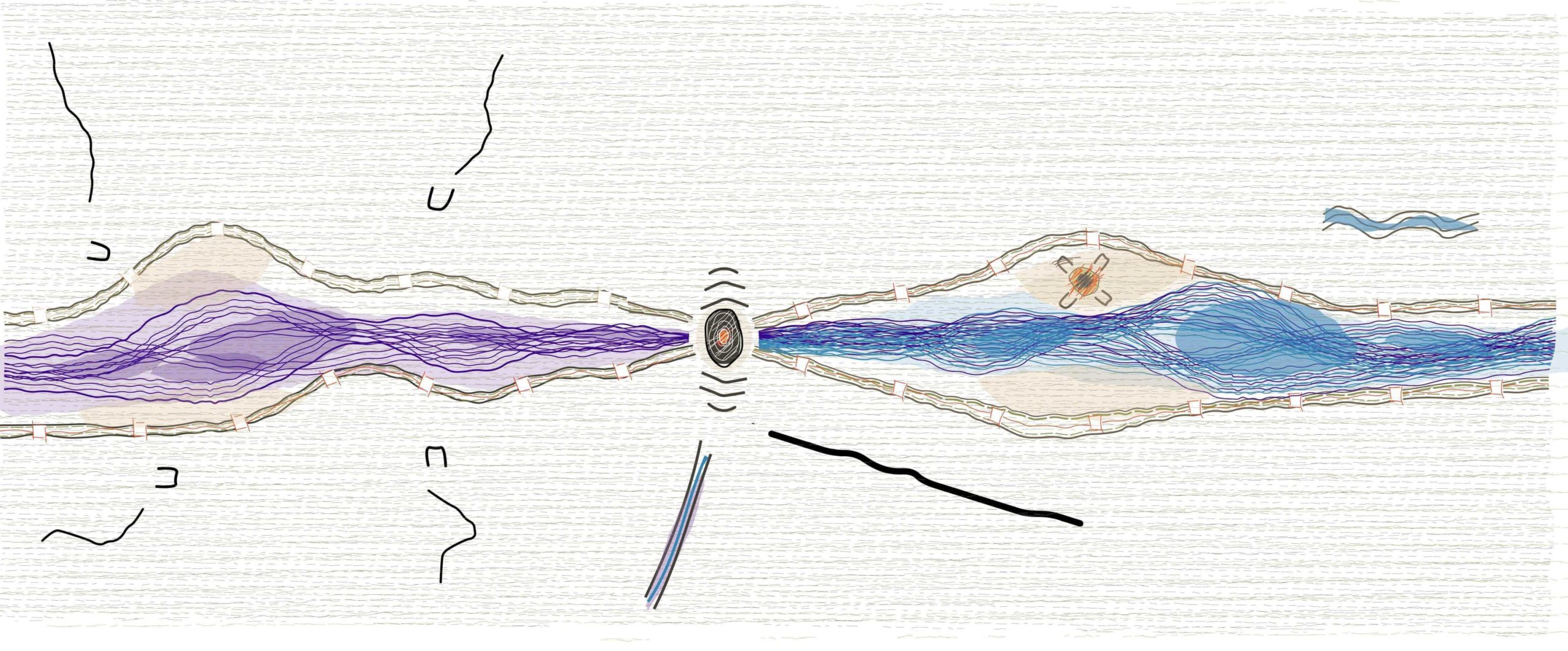

An architectural discourse that Belongs to Country will invigorate interrelated expression that defines and inspires connections to identity and place. Unique Australian architectural expressions may indeed flourish with built form that distinctly belongs to place, is of place – an architecture that is part of the ambiguity of what is human, and what is nature. Belonging is about relationships, with connections beyond Western surveyed boundaries. When built form Belongs to Country it intuitively embraces its obligations to the health and wellbeing of Country, as family, so it is imperative that the architectural profession engage with Indigenous worldview philosophies such as yindyamarra winhanganha. Designing From Country requires that we start with these relationships. What unfolds will be an architecture that is enriched by, specific to and designed from the original place and cultural qualities from which it came. Engaging with place through a First Australian worldview is part of my custodial obligations to reinforce the connected qualities of the landscape and kinship to which I belong. This way of thinking extends beyond the binary proposition of the superior human being arrogating dominating nature to instead strengthen relationships between that minimise the disruption of environmental ecologies. Excitingly, the expression then becomes about this ambiguous state, nuancing the constant tension between and the vast array of ways this can unfold.

CUSTODIAL ARCHITECTURE IS AN EXTENSION OF THE INDIGENOUS SOCIAL CONTRACT

My experiences in commercial practice is that built form must find its place within this relational context, fit in, and as such be accountable for and establish ways to relate to its spatial context. Shaped by a sociology of spatial and environmental considerations,4 design thinking then becomes informed to the Indigenous culture and character of place. An example of this would be a project near a river. The architecture can identify as being part of this tributary system. Here, the architect must collaborate with Traditional Knowledge Holders to find ways for built form to connect to the stream, and take responsibility for all that resides within these spaces. These practices deliberately strengthen natural and human connections to each other, at times blurring one from the other, to bring forth the sense of reciprocity. Design explorations essentially then become a process of refining and reinforcing the cultural practices of reciprocity to enact Custodial Architecture – embedding the idea that built form is part of the landscape, itself belonging and in a reciprocal relationship with people and nature.

Individualist social structures are like an infliction of mass narcissism, blended with apathy and complacency.5 The architectural story that unfolds here is often transactional, and disconnected from its context. While the architecture expressive of a detached liberal social structure reflects the free individual model, the cost of the distance between humanity and nature may well be the dissociating factor distancing us from our very own identity, and sense of belonging to place. Separating us from our core responsibilities and custodial obligations. Instead design approaches can become intuitive as we respond to and connect with the character of place, understanding what is best for the collective wellbeing of an integrated social and environmental ecology. Belonging to Country sparks and gives rise to the design of our built environments through an Indigenous lens based on relational foundations like yindyamarra winhanganha. This way of thinking can genuinely define us, our identity, our architecture and guide us to captivating, thought-provoking propositions. Designing from Country will undoubtedly see the unveiling of exciting and compelling architectural expression with purposeful resolve which will be understood as an extension of nature, rather than an imposition upon it.

NOTES

1 Tim Flannery, The Weather Makers: The History & Future Impact of Climate Change, 2008, Chapter 22, p 209

2 As told to me by Dr Stan Grant (SENR) April 2021, and public address in December 2021 at the rescheduled NAIDOC event in the Botanical Gardens, Sydney. Also noted in The New Wiradjuri Dictionary (2010) Stan Grant AM and Dr John Rudder, pp 469, 485.

3 Tyson Yunkaporta, Sand Talk – How Indigenous Thinking Can Save the World, 2019, p 20

4 Better Placed, Connecting with Country, Government Architect New South Wales, Issue no. 01-2020 Draft for Discussion

5 Simone de Beauvoir, The Ethics of Ambiguity, Part 1, p 29. “There are people who are filled with such horror at the idea of a defeat that they keep themselves from ever doing anything. But no one would dream of considering this gloomy passivity as the triumph of freedom.”

Craig Kerslake is a Wiradjuri architect and managing director of NGULUWAY Designinc. Craig draws upon his cultural heritage, community and knowledge of what Aboriginal people refer to as Country. Within a team setting, he brings this forth with spirited innovation to inform spatial design and architectural form with unique expression that finds resonance with all Australians. His cultural overlays often draw design thinking to the unexpected and provide positive outcomes focused on Aboriginal-centred qualities, spatial unity and scales of social engagement