Architecture as host

Can we improve the responsiveness of our architecture through our own experience?

Recently, in the middle of a bushwalk with friends through steeply folded country, I took my shoes off to go barefoot for a while. Suddenly, long protected toes and soles were registering every subtle shift of gradient, tiny stones, decomposing bark and leaves, delicate twigs. I continued, wincing, with tender footfall; reflecting on our usual way of being in nature as onlookers and wondering how Wurundjeri may have experienced this country in pre-European times. There was a breeze. I was aware of its note as it blew across my ear. I could feel my hair lifting, the roots straining slightly. Perhaps there was an increased receptivity – we had agreed at the start that this would be a silent walk, to be as present as possible.

Usually we tend to separation, lacking attentive sensing – listening, observing, beholding – and literally being out of touch with ourselves, our communities and our environment. This in turn is reflected in our architecture. In a sense, our buildings are us; they speak through their gestures.

Can we improve the responsiveness of our architecture through our own experience?

In a small, tall, and darkened room, staggered lengths of muslin were suspended. A film was projected onto these delicate screens. The camera had been placed on a rise among trees looking out to a site where a massacre of Indigenous people took place.

In the foreground was an ancient gum, wired for sound, tiny microphones recorded and amplified the inner activity of the tree as well as the leaves brushing the branches in the wind. We could hear the fluids fluxing and flowing through the gum, insect activity, and other mysterious sounds from the inner life of the tree. White gauze bandages were wrapped around trunk and branches as if to protect open wounds; the tree perhaps in a process of healing. The camera changed from being still and focused on the tree to panning slowly through the bush, sometimes nervously, out to the massacre site giving us an uneasy sense of looking out from hiding as fugitives or being pursued and spotted by the perpetrators. We were drawn into relationship with the old tree, witnessing then bearing these ‘memories’ for almost 200 years.

This work gave us a surprising perspective on nature, presence and consciousness and an affinity with a traditional Indigenous perception of the animated beings of Country, or what we can think of as the community of interwoven beings who make up life on earth. This community includes us with our responsibility for creative caring or careless destruction.

‘The witness tree’ by Judy Watson, was part of an exhibition ‘Myall Creek and beyond’ at New England Regional Art Museum in 2018, reflecting on the massacre of 1838. This massacre is remembered each year at its site in northern NSW by a gathering including descendants of victims, perpetrators and others concerned with the task of healing. A poignant visitor experience of sorrow and intergenerational reconciliation.

Architecture has a capacity to go beyond the merely visual and functional, to resonate with the complex becoming of the history, cultures, peoples and Countries of Australia. In its processes and forms, it can give voice, vision, and emotional range to communities finding or recreating themselves. It can be a catalyst for ‘upwaking’.[1]

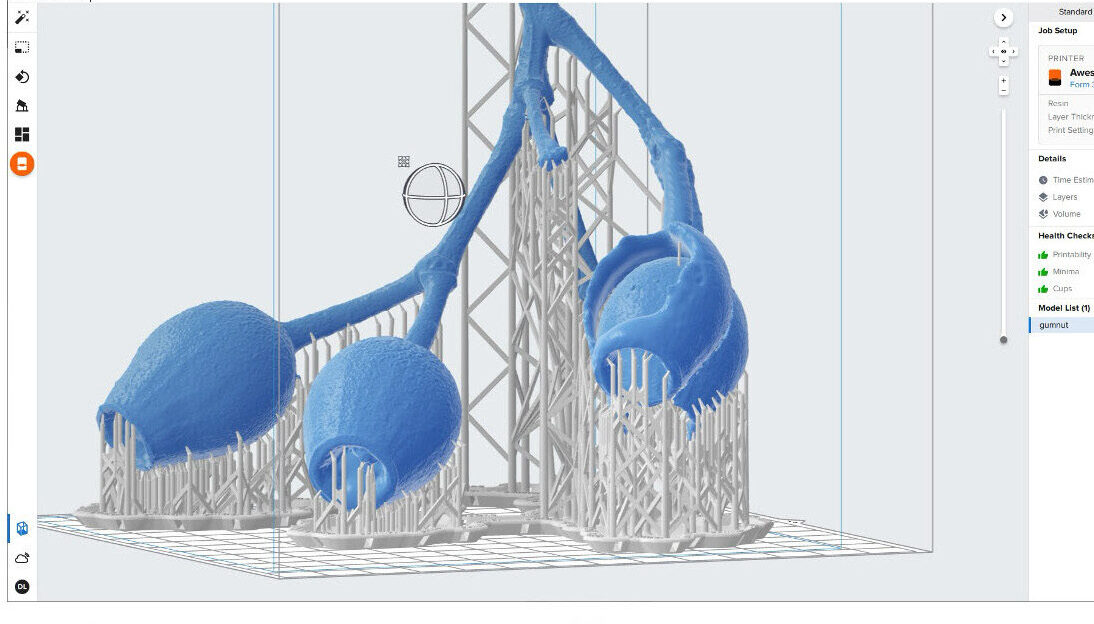

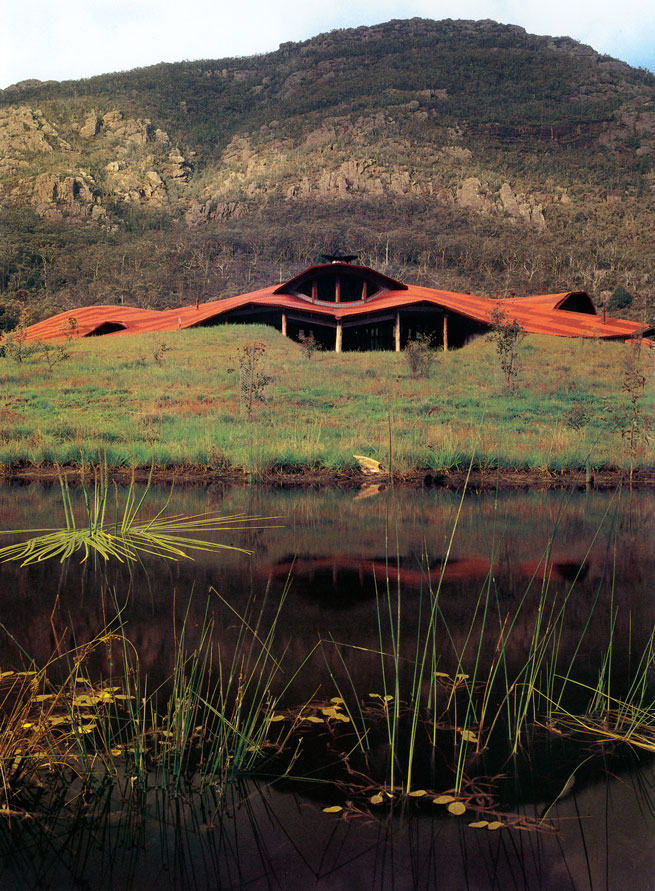

The Brambuk Living Cultural Centre in Gariwerd, western Victoria, for example, embodies the stories and totems of its five communities, who were participants in an 18-month-long series of workshops to develop its design. In its animated shadows, and the buckling, bearing and lift of its forms, it holds the suffering and mourning of the tragic past, as well as the challenges and hope of healing. This is an ongoing task; reconciliation and architecture both require maintenance, nurture and renewal.

The year Brambuk opened, we began working on a new cultural centre for the Uluru-Kata Tjuta World Heritage National Park. Uluru is sacred to Anangu people and a place of pilgrimage for all Australians and many visitors to Australia.

For a month, we lived and worked with the Mutitjulu community to design the centre as a celebration of joint management, a coming together of Western science and traditional wisdom. It was to be an Anangu place where they would be seen as the hosts inviting and welcoming Minga[2] to their Country, to share an understanding of their culture. It would not be just a tourist place that tolerated Anangu as had been the case in the past.

In those years, largely ill-informed tour bus drivers carried considerable interpretative and financial power compromising Anangu cultural and economic integrity.

The challenge here was to facilitate a collaborative process to create a building which wove together living spiritual and physical connections with Uluru, the sacred country and its people. This demanded a willingness to improvise with Anangu, in response to the events, questions and opportunities of each day. This willingness created a space of trust, synchronicity and inspiration. Personally, I found a rhythm of early morning contemplation and meditation helped me to be fully present to what was needed to allow the project to unfold out of each moment, each encounter.

As a team, we worked closely, joining daily to share our experiences and thoughts about how to enliven, warm and expand the shared, middle space.

On one occasion while walking the site with Elder and artist, Nelly Patterson, she began to talk passionately about the way the building needed to express the notion of Anangu and the NPWS rangers ‘working together as one’. Demonstrating, she cupped each of her hands and curved them into one another like two interlocking arms of a spiral galaxy. This was a vital moment. I immediately sketched her gesture in the sand at our feet. This form became the seed for the unfolding design.

Whether we see the arms as being Liru and Kuniya, the two sacred serpents of Tjukurpa [3], Indigenous and non-Indigenous, inner and outer, spirit and matter; they both embrace the shared space – they are distinct, complementary, yet one.

Habitual ways of seeing had to be abandoned so we could let the stories of Anangu and the living presence and ancestral beings of Uluru inform the emerging design.

In a culture where architects may feel obliged to create visually novel and arresting objects designed to have visitors reaching for their mobile phones,[4] we might aspire to create collaborative processes and design buildings which resonate with the authenticity of culture, community, and Country. The experience could evoke a lively ‘conversation’ between the building and its visitors, place, spirit and culture.

As architects, as human beings, the 21st century invites us to respond to contemporary complexity with sensitivity, fluidity and the deep silence of listening. We can then invite connection, authentic presence and the dynamic of becoming into all our creative work.

NOTES

[1] Ben Okri used the term ‘upwake’ in his 2019 novel The Freedom Artist as a call for a radical shift in consciousness.

[2] Tourists or visitors, literally ants, due to the appearance of visitors in tiny moving lines on the Uluru climb before it was closed on 26 October 2019.

[3] Tjukurpa is the foundation of Anangu life and society. It has many complex but complementary meanings and refers to the creation period when ancestral beings created the world as we now know it but also refers to the present and future. It encompasses religion, law and moral systems, it defines the relationship between people, plants, animals and the physical features of the land, how these relationships came to be, what they mean and how they must be maintained.

[4] Photos are not permitted at the Uluru-Kata Tjuta Cultural Centre.

Gregory Burgess practises architecture as a social, healing and ecological art. His projects, including housing, community, cultural, Indigenous, tourism, educational, health, religious, commercial, exhibition design and urban design, have received many awards. These include the Sir Zelman Cowen Award for Public Buildings, the Victorian Architecture Medal for the building of the year, and the Australian Institute of Architects Gold Medal. He is recognised with a Member of the Order of Australia for services to the community for environmentally sensitive building design.