20 October 1933 – 20 September 2021

The Canberra architectural community has lost a skilled designer and one of the world’s best organic style architects. Laurie Virr was the antithesis of what popular media would have you think of when you hear the word, architect. Yet he was a peerless architect who dedicated his life to finding the purest expression he could through architecture. He was a generous teacher, and dedicated mentor to countless young architects over his career and has left a legacy that won’t easily be forgotten by those who were privileged to know him. Having the honour of having him as my own mentor and friend will be one of the highlights of my career.

Canberra in the mid-century was a place of great bravery, innovation and considered design. The burgeoning city attracted young men and women including architects. Laurie Virr chose to call Canberra home, being attracted to the opportunity of working within a planned city and the design legacy of Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin. Like the Griffins before him, Laurie was a skilled designer of the American organic style of architecture, made famous by architects such as Frank Lloyd Wright.

Laurie Virr was born on 20 October 1933 in London, England. Born into a poor, working class family, Laurie’s early years were often spent without a lot of food, clothes, and warmth. Instead of hardening him to the world, Laurie developed a generosity of spirit second to none. He credited his survival with being an accomplished student and later a skilled athlete. Laurie had an interest in architecture from a young age, but when he graduated top of his class and won a place in a technical high school, he chose to study engineering as it would provide better job opportunities and enable him to support his struggling family. Graduating as an engineer, Laurie struggled under the entrenched UK class system. Through running, he found a new outlet for expression where everyone was equal on the track. He competed in meets across Europe and the UK, and caught the eye of Australian trainer Percy Cerutty at the 1958 Commonwealth Games. Cerutty suggested Laurie move to Australia to train for the Olympics.

Like so many others, Laurie came to Melbourne as a Ten Pound Pom, immigrating to train under Cerutty for a chance to compete at the 1960 Olympic Games. Sadly for the sport, Laurie broke his foot in the lead-up to the trials. With his Olympic hopes dashed, Laurie turned his attention back to engineering and worked for some time at Bates, Smart & McCutcheon. He also met his partner in life, Mary who he credited with him becoming an architect. Mary, a teacher, vowed she wouldn’t marry a man who didn’t love what he did and encouraged him to retrain in the profession he had always felt drawn to.

Unable to get credit for his engineering studies at RMIT, they returned to England where Laurie studied at the Kingston School of Art in London. He later travelled to the USA in search of the necessary work experience, given employment with Malcolm ‘Mac’ Wells, a pioneer of earth-sheltered architecture and a fellow follower of

Frank Lloyd Wright. The two developed a lifelong friendship, with Wells even sponsoring a road trip across America to visit highly regarded architecture before Laurie and Mary returned to Australia.

Believing strongly in the relationship between master and apprentice, Laurie was both a dedicated student and teacher. On returning to Australia, Laurie established his practice in Canberra. Combining his engineering training, and what he had learnt from the masters of organic architecture, Laurie’s singular focus remained residential architecture.

One of the first projects Laurie designed in Canberra was the Andrews’ House in Juad Place, Aranda. It is sited adjacent to another significant piece of Canberra’s architectural legacy, the Paterson House by fellow emigre architect Enrico Taglietti. The house was at first denied planning approval on the grounds that it did not look like a house, and the kitchen was internal and lit by a generous skylight. Planning regulations of the day were based around the Country Women’s Association guidelines that suggested kitchens should be placed to allow housewives to enjoy a view while cooking. Thankfully it was approved on appeal, and the house now rests as a quiet reminder that there isn’t one formula for house design. The house is designed around a triangular module and was shaped to meet the clients’ desire to retain all trees on the bush block. 72 of the 73 existing trees were retained and combined with a low shingled roof and local bricks, ensured the house sat gently in the landscape from the outset. Drawings and photographs of the house were chosen for exhibit in the 1972 Commonwealth Institute in London.

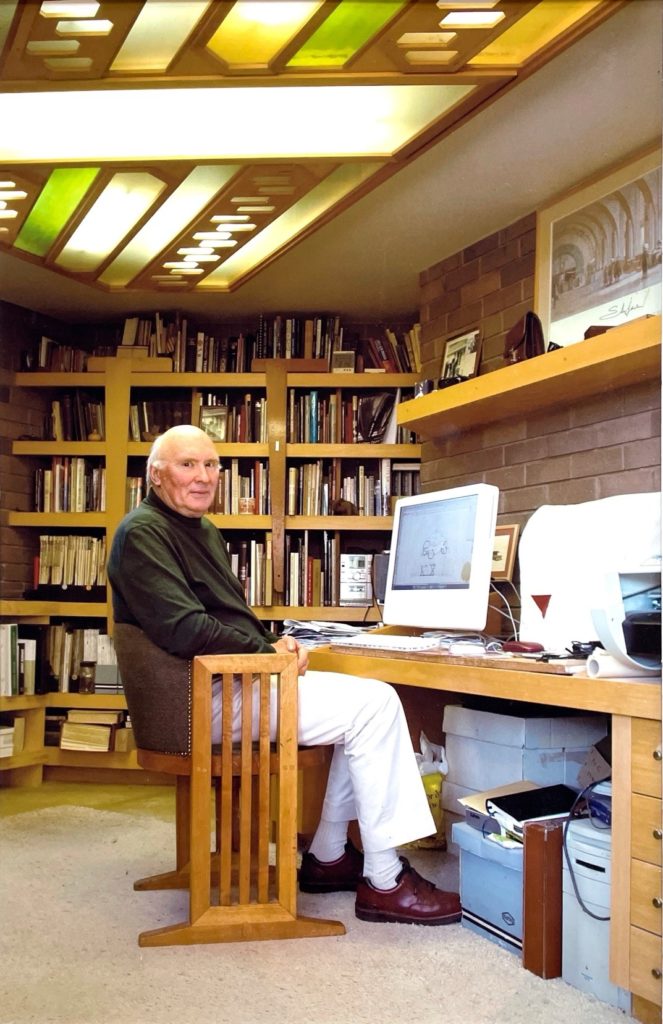

Designing homes around Australia and the US, Laurie worked from the house he designed for his family and built mostly by his own hands, Rivendell, in the Canberra suburb of Kambah. Not only was the house designed to meet the brief given to him by his wife Mary but was also the same size as government-funded housing of the day. Laurie was a fervent critic of the Australian approach to both social and indigenous housing. He participated in several architectural explorations of alternatives to both issues and used his own home to show that meaningful architecture could be provided to meet government requirements for social housing of the day. He also had a deep social and environmental conscience and described the brief for his own house as “…The requirements were for an environmentally responsible house, having living, dining, kitchen, laundry/utility, 2 bedrooms, a single bathroom, a studio, and a carport capable of sheltering one small vehicle. The latter is all that can be justified by any environmentally responsible family. I determined to design a passive solar dwelling having an area no greater than that of the government financed housing being built at that time, but one that displayed in unambiguous terms what I considered to be Architecture: a solar house that did not look as though it had been designed by a mechanical engineer.”

Rivendell presents a complex geometrical plan based on a hemicycle, with a wonderful play of interpenetrating forms, and is a superb example of solar passive architecture. The house is built deep into the site on the southern edge, taking full advantage of the insulative value of earth berms, and opens to the north to capture the maximum amount of warmth and light. Much like the Andrews House in Aranda, Rivendell presents a delightfully inconspicuous face to the street, allowing passers-by to instead enjoy the views across the valley to the distant hills. In 2016, Rivendell was awarded the Australian Institute of Architects ACT Chapter’s Enduring Architecture Award and is listed on the ACT Register of Significant Architecture. The house has been published many times in both Europe and the USA, was featured in the Australian exhibit at the 1983 Paris Biennale, and played host to close to 2000 people from around Australia and the world.

Laurie was a firm believer that architecture was the highest form of art and that all people should have access to it. There was none of the elitism made famous by others, and he dedicated much of his energy to supporting young architects and others with whom he shared a deep passion for the organic style architecture most often associated with Frank Lloyd wright. For Laurie though, it was actually architect Aaron Green who was the greatest influence of his own architecture. Laurie taught at many places including the Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture in Spring Green Wisconsin, the University of Oklahoma, and the University of Washington.

This generosity, both of spirit and of design, epitomised Laurie Virr. He was an architect without equal and a man who never faltered in his desire to inspire others. He was an architect, teacher, environmentalist, friend, husband to Mary and much-loved father to Alexander. He continued mentoring until his final days, and the legacy that he leaves behind will not be easily forgotten by all those who knew him. He was an innovative and original thinker and always prepared to stand behind his convictions. His final words to me, days before his passing, were:

“Australians just don’t seem to think architecture is for them. How do we enthuse a nation who for the most part have no interest? We must be the flag bearers and fight for the change!”

In light of restrictions on public gatherings, a chance to gather and celebrate Laurie’s life will be held early in 2022.

Vale Laurie Virr.

Obituary by Shannon Battisson, RAIA