Michael Croft recently had a chat with Harry Mills, a designer and PhD candidate, passionate about regenerative, and environmentally responsible design. Harry’s current project looks at resource recovery of marginalised and under-utilised timber for use in the built environment.

MC: Tell us a bit about your journey in Architecture to date?

HM: My interest in architecture and timber really began at an early age. I grew up in workers cottages in and around Brisbane surrounded by native pine and eucalyptus trees. The materiality of the houses, nature and fauna all had an impact on my journey into architecture. I began my training with a Bachelor of Design (Architecture) at the Queensland University of Technology (QUT), and I immediately looked to put the real-world training into practice where I worked alongside my studies. I managed to get my foot in the door early on and have been fortunate to work at some great firms in Brisbane, and abroad in Budapest, Hungary, São Paulo, Brazil, and Beijing, China.

I have also completed a Master of Architecture at QUT. My work focused on advocacy for the use of timber, particularly the use of mass timber in built environments locally in Nambour, Australia and overseas in Jinan, China. I looked at local manufacturers and designers’ opportunities, speculatively proposing a future where Australian exports could be ones used to sequester carbon rather than emit. My interest in materials and sustainability led me to study a Graduate Certificate in Timber Processing at the University of Tasmania (UTAS). The course provided specialist training in timber design and construction and provided an overview of the timber resource supply chain in Australia.

I work as a designer, researcher and educator in academic and industry sectors, leading projects looking at the use of timber in construction. I am currently completing an Australian Research Council funded PhD with the Future Timber Hub and School of Civil Engineering at the University of Queensland (UQ).

MC: What is your research topic and when will you be finished?

HM: My research is on resource-conscious design strategies for the recovery of marginalised and underutilised timber for building products in Australia. I’m looking at plantation softwood species Pinus Caribaea and Elliottii, or Southern Pine as it’s more commonly referred to. Southern Pine is grown throughout the South-East Queensland and Fraser Coast region and is predominately used for board and plank products that go towards structural framing in residential houses.

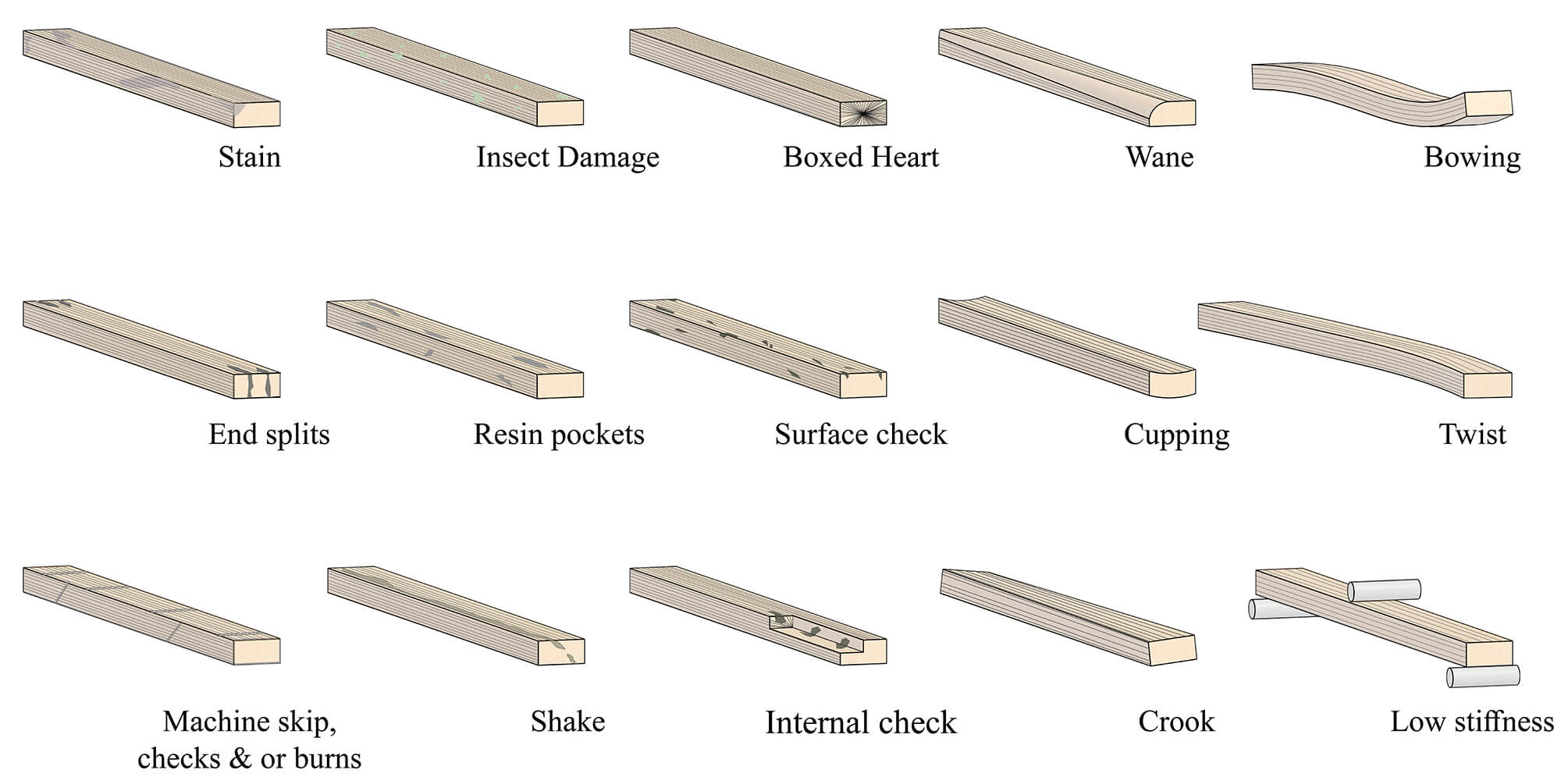

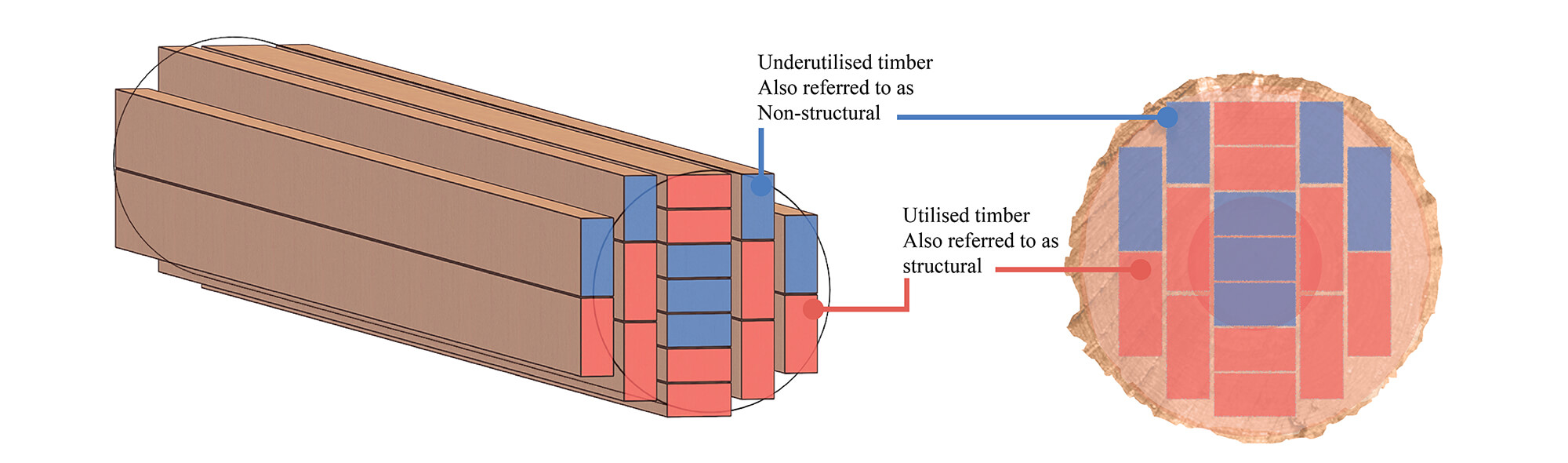

My main focus area is the recovery rates of timber across the product supply chain. Structural grading of sawn boards results in a preferential selection of timber with high-density qualities and minimal growth and processing characteristics. Concurrently, sawn boards with low-density fibres and more growth and processing characteristics will typically fail structural grading criteria. While demand for structural timber is high in Australia and abroad, there is little demand for timber that fails structural grading. The timber of this class has low market perception, low fiscal value, and ultimately short longevity in terms of lifespan. I call this resource underutilised timber (UUT).

I’m finding ways to maximise the amount of wood we can extract from each tree for timber building products. Already timber is becoming a more affordable and accessible material for different building typologies through mass timber construction, and it will help the industry reduce its overall carbon emissions. UUT can contribute through additional building products with greater resource recovery and help lock up and sequester carbon long-term. I have been working on this with my PhD advisors Dr Joseph Gattas and Kim Baber at UQ, and I am completing the project in December of this year.

MC: How will your research impact the practising architect?

HM: I have developed through my research methods for architects, engineers, and builders to incorporate UUT into building design. I have been able to achieve this through different means. In 2018 I was awarded a Gottstein Fellowship to investigate the state-of-the-art of timber supply chains through North America, Scandinavia, Europe, and the UK. I met with leading professionals ranging from foresters, millers and manufacturers, architects, engineers, builders, artisans, educators, researchers and policymakers. This investigation helped me identify several pathways for UUT uptake and resource-conscious design strategies for the use of timber in construction.

One of the strategies is a digital tool that will be released open-source soon. The tool loads up the practising architect and engineer with information on specific timber products for residential and mass timber building design. It links products back to the tree through supply chain mapping, structural design analysis, and volumetric estimation per building. The tool can introduce the user to UUT and its meaning for the building design and other notable features. In addition to the tool, my research contains practical recommendations for architects, engineers, and builders to absorb more significant UUT volumes.

Above: UUT Characteristics. figshare. Figure. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12987671.v2 | Harry Mills (2020)

Below: Resource Breakdown Diagram. figshare. Figure. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13012838.v1 | Harry Mills (2020)

MC: What opportunities for improvement exist within the manufacturing and construction in Australia?

HM: Globally, building activities are responsible for around 40% of greenhouse gas emissions, and materials and construction account for 11% of that. Herein lies enormous opportunities to incorporate more renewable building products to reduce embodied carbon in construction.

Sustainability initiatives only go some way to improving traditional building methods and systems. Opportunities exist for designers to put into action resource-conscious design by thinking regeneratively to have far greater impact on projects and their communities.

For instance, the use of timber can be expanded across all building typologies in the country. Engineered wood products are an alternative option to high embodied carbon materials like steel and concrete. Indeed, with further exploration, designers can delve into using other renewable materials like bamboo to help shift the needle on climate change abatement.

MC: What are some notable built projects or academic research going on in the timber industry currently?

HM: Locally, there is the Future Timber Hub at UQ, the Forest Product Innovation stream at the Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, the Centre for Sustainable Architecture with Wood at UTAS, the National Centre for Timber Durability and Design Life at USC, the Centre for Innovative Structures and Materials at RMIT, Forest Wood Products Australia, the Gottstein Trust and WoodSolutions just to name a few. The old aircraft hangars at Archerfield and Eagle Farm in Brisbane are wonderful short-length timber structures. Boards like this are often discarded due to their length; however, they have some terrific properties suited for applications similar to the hangars’ trusses.

There is quite a lot happening overseas. Two recent research projects that I love are the Zippered Wood Project by the HiLo Lab at SALA at the University of British Columbia and the Urbach Tower by ICD at the University of Stuttgart. Other groups worthwhile looking up are the Digital Structures group at MIT, CNMI at Cambridge University, TUMWood at TU Munich, DTC at TU Kaiserlautern, Gramazio Kohler Research at ETH, IBOIS at EPFL Lausanne. In practice, Intelligent City is a cool company to keep an eye on.

MC: Would you recommend post-graduate research pathways to others within the architecture industry? What has been the most valuable experiences to date?

HM: Undertaking higher degree research can be very rewarding and provide a platform to participate in meaningful, transformative work. It does not necessarily have to be a PhD project, as this can be quite a long journey – but it could be a short term intensive course on a topic of interest, graduate diploma or a certificate. As part of a PhD, research training has many qualities that can serve you well as a designer. Critical thinking, problem-solving, data gathering and analysis, networking, writing, and public speaking are all traits I’ve had to develop over the last few years. One of the most valuable experiences for me has been the opportunity to collaborate and connect with people worldwide. To be in touch with new discoveries in construction and the state-of-the-art in renewable materials for architecture is an exciting space to be operating in.

MC: How can we stay in touch with your research outcomes?

HM: I’m available and happy to chat with anyone interested in my research or generally. You can find me on LinkedIn or sporadically across the socials @harryfmills.