As we walk from Salamanca up to the Farmgate market, our third morning together on the Dulux Study Tour is sunny and crisp with leaves crunching underfoot. We immediately seek out coffee, and shortly thereafter another coffee, before embarking on our first architecture tour of the day to the beloved Esmond Dorney house built in 1978.

Arrival at Dorney House is a steep hike up an extensive property that has us all puffing as Keith distracts us with anecdotes about his time as a caretaker of the house a decade ago. As we gain height, we glimpse tiny sailboats tack across the Derwent River and trail runners jog by us on the now council-owned reserve. As we round the corner on the final switchback, the structure appears perched on a hill amongst a rambling native garden. Round in plan and with a completely glazed façade, the building is almost characterised more by its transparency than by its presence. Strokes of blue water sketch in the horizon line beyond a sunken lounge and untouched melamine kitchen. The white scalloped roof is a cloud-like structure that appears as if it could float away but for the thin steel trusses tying it to the ground.

By reflecting and echoing the textures and colours of the surrounding sea and sky, Dorney House is a humble and elegant example of how architecture can be recessive in the context of great landscape. Its ethereal minimalism is a direct contrast to the subterranean maximialism of our next building tour – MONA.

As we approached by ferry, the layered hills became foggy and rain began pelting the windows noisily. The virtual inverse of the Dorney House, MONA is a nestled into the cliffside of the Derwent River banks and anchored deeply into the earth. A completely different but equally thoughtful response to landscape. As wind turns umbrellas inside out, we dash up the steps into the vestibule of the museum to land in sheltered warmth.

Once inside, we arrive at the Void – a space characterised by depth, darkness and texture. It is a type of sensory architecture that prepares visitors for the art collection to follow. We clambered up and down thick folded steel stairs and wandered through weeping stone tunnels. It’s often unclear what level of the gallery you are on and how deep below ground you may be, but the disorientation lends to the enchantment of it all. The architectural journey is punctuated (as always, at MONA) with irreverent art and fervid conversation.

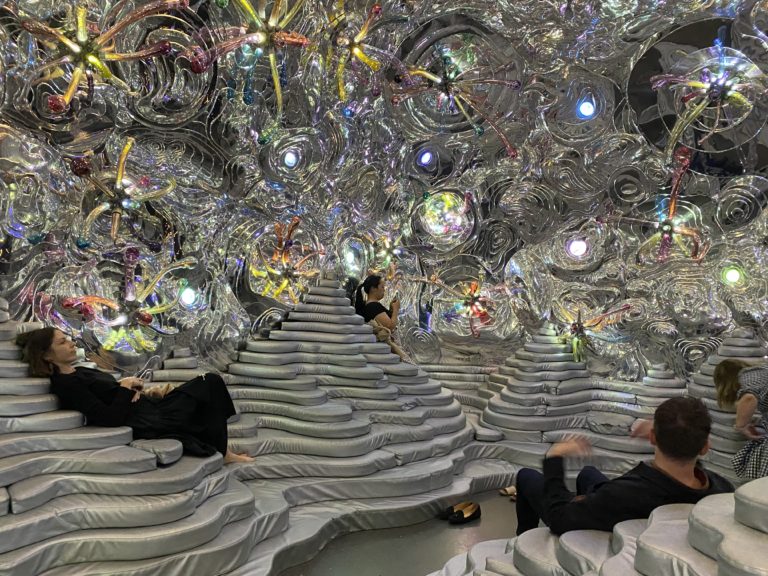

We’re then met by MONA guide Led Emmett, who takes us around the campus sharing his knowledge and insights into the various projects. As dinnertime approaches, we’re led to Faro restaurant via James Turrell’s bridge-like piece, Beside Myself, an appropriately ceremonious entry into the recent extension. The restaurant features a vaulted glass space on the water, purpose-designed to hold Turrell’s iconic orb-shaped piece, Unseen Seen, and also housing his additional work, Event Horizon. The Turrell experience can be ordered off the menu, and as lovers of light and space, we architects are giddy to experience them all.

Dinner is a performance in food and art. As courses come out, live performances take place among the tables while members of our party are invited off in pairs and groups to experience the Turrell pieces. Each plate is a beautiful experiment – colour, texture and temperature all being playfully composed. One of the best parts of the night is watching the faces of those stumbling out of the orb and back into reality after an exquisitely disembodying experience that surely solidified many friendships in the group.

It wouldn’t be a final night in Hobart without the iconic MONA experience, and this one was a truly unique and special one. Our time in Tassie has been characterised by crafted, local projects and the kindness shown to us by local architects and alumni, for which we are deeply grateful.

Madeline Sewall