Skin deep

I was making a left turn onto Lygon Street, towards East Brunswick, when my passenger, one of three founders of our Stockholm-based architecture practice, began to gesticulate wildly at a row of silver, waveshaped fins attached to the facade of a five-storey apartment building, exclaiming in surprise, “What is that?!” Our office does a lot of housing research, which often requires constructing big data sets and large archives of architectural drawings in order to analyse trends.

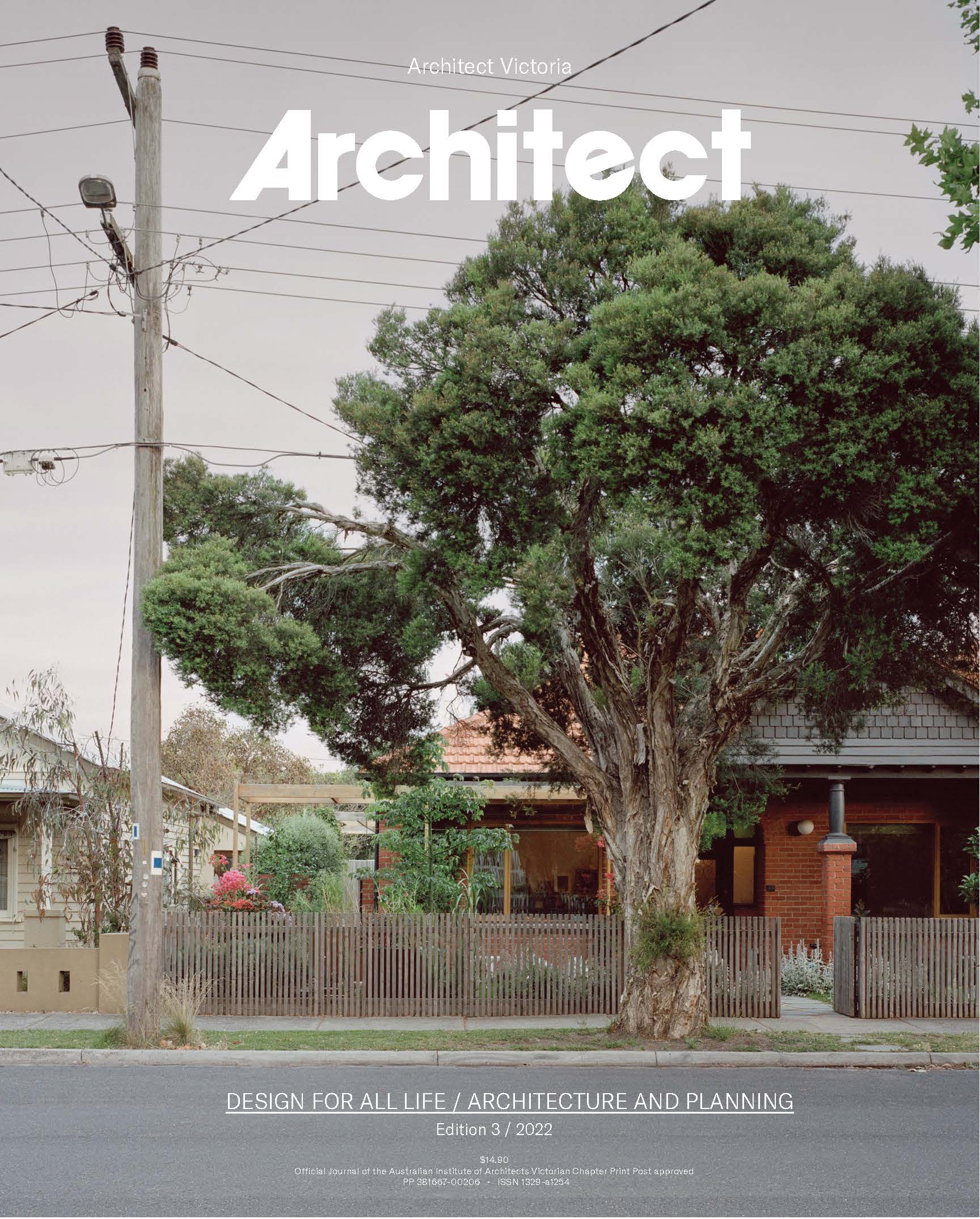

But turning the corner on that warm Melbourne autumn day, we didn’t need any fancy methodologies to identify this architectural phenomenon, writ large across the walls of the city. This very public gesture not only repeated itself across the facade of the adjacent building, where it shifted from waves to lines, but continued up the street and through neighbouring areas, jumping municipal boundaries: a city-wide supergraphic that the Victorian planning system refers to as “facade articulation”.

A deep, fine-grained rhythm

Upon returning to Stockholm, unable to let go of this striking – and frankly rather strange – phenomenon, I started to dig. I studied urban design in Melbourne in the early 2000s, but at that time I saw this kind of language as self-explanatory.

Now I wanted answers. Facade articulation, I learnt, is buried deep within the Victoria Planning Provisions (VPP) and the municipal planning schemes that the VPP structures.1 It predominantly seems to come up in the schedules to the Design and Development Overlay (DDO) and the Development Plan Overlay (DPO) and sometimes in sections dealing with the detailed design of housing (54.06-1, 55.06-1, 58.06-1) or local planning policies. Its frequent use confirms that articulation is not just an arbitrary architectural trend; it’s a regulated requirement, mandated by the state, linked to the delivery of “building design and siting outcomes that contribute positively to the local context… [and] enhance the public realm.”

In Merri-bek (the soon-to-be renamed City of Moreland), facades are to be articulated in order to “achieve a good interface with and surveillance of the public realm, including maximising opportunities for active frontages” (15.01- 1L); to “minimise visual bulk impacts as seen from neighbouring rear secluded open spaces” (15.01-5L); to “provide visual interest,” “create a pedestrian scale at street level,” and “equitably distribute access to an outlook and sunlight” (Schedule 1 to the Activity Centre Zone, Precinct 10: Pentridge Village); to “break the visual bulk, and give rhythm to the development” (DDO5); to “add to the visual richness of the area” (DDO6); to “reinforce the prevailing fine-grain pattern of subdivision and buildings” (DDO18); and to differentiate upper levels “from the building’s street wall” (DDO19). Articulation is also invoked in DDO24, where “New buildings should adopt solid architectural expression that emphasises the street edge through the use of recessed balconies, framed elements and solid balustrades,” and at DDO29, DPO11, and DPO12, which repeat earlier formulations regulating grain, bulk, and surveillance.

In Yarra, articulation appears to be treated more neutrally than in Merri-bek: DDOs 25, 30, and 35 to 40 all reinforce that articulation (along with building siting, scale, massing, and materials) is an area through which design excellence can be achieved, rather than an aim in itself. In the City of Darebin, DPO12 describes articulation in terms of “punctured facades” wherein “floors should be distinguishable,” while DDO3, DOO16, and DDO17 usefully define articulation in terms of “a suitable ratio of solid and void elements” and “a well-considered combination of horizontal and vertical building elements,” also advocating for “the application of a limited palette of materials.” This latter point indicates that even articulation has its limits, something confirmed by the City of Yarra’s DPO15, where development should “avoid highly articulated facades above retained heritage buildings.” There can be too much of a good thing, it seems.

Articulation emerges, from this brief regulatory review, as an architectural operation that does a very specific job in Victoria. Firstly, articulation is a visual patterning that is achieved by manipulating solid-void and horizontal-vertical ratios within a volume or facade. Secondly, this operation is meant to induce a sense of the building whereby it is perceived to be both very interesting but also smaller than it is. Thirdly, articulation exists to materialise idealised historical property relations; in particular, its geometric logic should represent a fine grain – or tight – subdivision, regardless of the reality.

For architects, being asked to articulate a facade strikes me as a little bit like being asked to read your kid a long, corporate Annual Report as a bedtime story: it not only takes an interest in owning capital way too far, it’s also damn-near impossible when that bedtime story also has to both be extremely interesting and appear to be much shorter than it is. An odd form of decorative, diminutive, regulatory property fetishism is at work here – and it suggests a troubled disciplinary relation between planning and architecture. This is the kind of task you would only give someone who you hope might fail.

An archiphobic absence

I look back through the three planning schemes on my desktop. Where is architecture, in all of this? I notice with some shock that the word “architecture” comes up only once in the VPP, where it is mentioned in relation to residential aged-care facilities (clause 16.01-5S). Australian critics often emphasise the fact that a limited percentage of buildings are designed by architects, but I can’t help but feel that the omission of architecture from the state-level provisions of the planning scheme is neither inclusive nor representative. Architecture’s regulatory absence has definite break-up vibes.

Was architecture banished sometime around 1968, when the utopia that the two disciplines had envisaged for themselves failed to materialise? Had this wayward lover been struck from public record in the hope that redaction might produce catharsis? Once all contact between the two had ceased, monikers and pseudonyms had crept in to fill the ensuing gap – The One Who Cannot Be Named became “the form of settlements” (11.01-1S), “types of housing” (11.03-1S), “development” (15.01-1S), “the city, places and spaces and facilities” (15.01-1R), along with “building design” and “buildings” (15.01-2S).

What is architecture from the point of view of planning when read through these monikers – that is, in absentia? Scouring clause 15.01-2S of the VPP searching for indirect references, I learnt the following:

- The building is an outcome of a process, the starting point of which is a site analysis.

- The role of planning is to ensure that the building does a range of things.

- The things that the building should do include supporting, enhancing, encouraging, responding to, protecting, providing, contributing to, and creating.

These acts are to be performed in relation to the objects of “strategic and cultural context,” “properties, the public realm and the natural environment,” resource recovery, stormwater discharge, “the function and amenity of the public realm,” “personal safety, perceptions of safety and property security,” “landmarks, views and vistas,” “transport movement networks,” existing vegetation, and the “cooling and greening of urban areas.”

In addition, pursuant to Clause 16.01-1S as housing, architecture is to provide amenity and incorporate “universal design and adaptable internal dwelling design.”

From the POV of the VPP, architecture is what we might – in theory terms – call ‘performative’.2 Rather than being something stable or static, architecture does things – it is what it does and it does what it is. When tangentially referring to the one who cannot be named, planning dreams of a discipline that protects the status quo, provides technical support to the environment, and creates security for people who already own property. It dreams of a lover with a decidedly neoliberal disposition, the total opposite of the digressive radical that architecture used to be. But is this the city it really dreams of, the photographic negative of architecture’s worst self?

It’s all about the optics

Is the building bulky? Is it interesting? Is it, or are those who might be within it, looking at me? And are they looking at me when I’m getting changed (voyeurism) or when I’m getting mugged (passive surveillance)? Does the building create richness? Does it have rhythm?

As any critical theorist will tell you, these are highly subjective and deeply normative judgements that are based on cultural and aesthetic preferences. The systems of classification that we use to answer such questions also classify us, producing us not only as differently racialised, classed, and gendered subjects, but also as perceiving ones. Perception itself, as historians of cybernetics like Orit Halpern remind us, is historically specific; and since the early twentieth century urban planning and design have acted as a key technology in formatting how we see, and what we can know about, the world.3

Urban design in particular has had a rather damaging tendency to de-historicise and essentialise its knowledge base as natural, intuitive, or common sense, but – like architecture, education, or medicine – it is also a disciplinary project with a particular political orientation and history. And that history is increasingly being interrogated in terms of its support for a neotraditionalist agenda that sought to reframe the relationship between the planning and architecture disciplines, partially through the introduction of a series of constructed conflicts on matters that were seen as central to an emerging neoliberal political economy.4 Those interests converged on the optics of capitalist land development strategies and the control of externalities, fed through a rhetoric of choice and diversity, appropriateness, wellness, and amenity.They ushered in a new world: one which itself is now appearing to disintegrate.5

In light of the conditions of our historical present – the interface-saturated existence of postpandemic life, the distributive politics of a property market that is effectively closed to entire generations, and the need to conceptualise new, higher density cultures of living and building in times of climate crisis, perhaps new bedtime stories need to be articulated. Perhaps planning needs to get back together with their ex, architecture. I think, given all that’s going on, there’s a good chance that architecture is no longer the irresistible, irresponsible maverick that left planning high and dry in the vacuum left by the perceived failure of modernism’s social project, just as planning has likely outgrown its obsession with wealth, status, and the regulatory cold shoulder. With all that’s going on right now, perhaps it’s time to articulate the terms of a future together. This is a question that extends well beyond the facade and the property boundary; it would require a vision about how we might all learn to live together. Despite our differences.

Notes

1 Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning. 2022. “Clause 15.01-2S Building design (09.06.2022 VC216)”, in Victoria Planning Provisions, Melbourne: State Government of Victoria. np.

2 This term was developed by J.L. Austin and popularised in part through its use in gender studies through the work of Judith Butler. See: Judith Butler, 1997. Excitable Speech: A Politics of the Performative, New York: Routledge. For an account of how “performativity” might be understood within architecture, see: Katarina Bonnevier, 2007. Behind Straight Curtains: Towards a Queer Feminist Theory of Architecture, School of Architecture, Royal Institute of Technology, Diss. Stockholm: Kungliga tekniska högskolan.

3 Halpern, Orit., 2014. Beautiful Data: A History of Vision and Reason Since 1945Durham and London: Duke University Press.

4 As Brian Tochterman argues, “While Jacobs and Florida deserve credit for highlighting the vibrant and dynamic life of the city in the face of unmitigated sprawl and narratives of urban decline, the time has come for a reexamination or reconsideration of their work, if not a reassessment of the planning profession and its purpose in the twenty-first century.” See: Brian Tochterman, 2012. “Theorizing Neoliberal Urban Development: A Genealogy from Richard Florida to Jane Jacobs” in Radical History Review 112 (Winter), doi: 10.1215/01636545-1416169.

5 “And yet we can argue that the neoliberal system is dissolving. Neoliberalism has, in the end, been abandoned, but not because it has been defeated by progressive forces on the grounds of its cruelty, injustices and repeated speculative crises, of which that experienced by Sweden in the 1990s was the first. It has been abandoned because it was inadequate in meeting a pandemic,” writes Göran Therborn in a recent anthology (translation from Swedish author’s own). Göran Therborn, 2022. “I systemskiftets avgångshall” [“In the Departure Lounge of a System Change”], in Bortom Systemskiftet: Mot en ny gemenskap [Beyond the System Change: Towards a New Community], Niklas Altermark and Magnus Dahlstedt, eds. Stockholm: Verbal förlag: 9.

Dr Helen Runting is an urban planner and urban designer working within the field of architectural theory and design. She is a founding partner in the Stockholmbased architecture office Secretary (www.secretary. international); a guest teacher at EKA in Tallinn; and a regular contributor to debates on urbanism, aesthetics, and housing politics.