Profit, publish, and perish

Words in the university sector

At a loss for words. Struck dumb. Speechless. Responses such as these, suffused with affective shock, suggest that you have apprehended something incomprehensible. You have no words readily available to describe what you are witnessing.

Certainly, 2020 erupted with a number of mediated events sufficient to render you, anyone, speechless: from raging bushfires and other incidents of the climate emergency, to a virulent pandemic that continues to spread, to the disturbing rise of populism, to the horrors of class, race and gender injustice. When words are the stock and trade required of your profession, then words must continue to be sourced, tamed and redistributed. Here the profession or sector in question is higher education, and the concerned intellectual labourer is the architectural academic. In higher education, organised as it is by the expectation that active researchers will publish, and that those published outcomes will satisfy an agreed metric of so many peer-reviewed articles per year, then clearly the time is never right to suffer a loss of words. You must represent even the unrepresentable to achieve career progression. In fact, there is a surfeit of words, a seething excess of the slippery, discursive things with something like two million articles published each year across more than 30,000 journals worldwide. The process is an arcane one relying on the unpaid labour of academics to undertake the blind or double-blind peer-review; blind being where the reviewer is given the author’s name but not vice versa – often the case with book manuscript reviews; double-blind assuming author and reviewer’s names are both concealed.

I say ‘unpaid labour’ here, in so far as such peer-review work is expected to be undertaken above and beyond the general day-to-day work demands of academia. There is the editorial selection of adequate reviewers, and then the agreement of two reviewers to accept the author’s work into their shared community of research, or not. Given time constraints and tendencies toward the territorialisation of knowledge domains, peer reviewers’ responses can be hasty, and even downright nasty. Still, double blind peer-review can be the means by which otherwise under-represented scholars are allowed into the academic game. Ideally, class, race and gender, and the unconscious bias associated with their designations, disappear under the covers of such blind-folded review.

Then there is the matter of where all this material, these thousands and millions of words, is being published. The most strategic researcher will identify those journals that result in a higher H-Index, this being – along other indexes such as the i10Index used by Google Scholar – the means by which the success of a scholar is generally recognised. This has to do with the reputation of the journal, how much the scholar has published and importantly, how often the scholar has been cited by other scholars. The system, perhaps unsurprisingly, is set up predominantly with the sciences and less with the humanities in mind. Architecture, it goes without saying, sits somewhere uncomfortably between.

Then there is the issue of what kind of obscure global system of power and influence you are subscribing to, depending on which journal you publish with, and who owns it. Just to mention two obvious choices, there are those journals, including The Journal of Education, Architectural Theory Review, Architecture and Culture, that are owned (and not always by choice, but because they have been traded onwards) by Informa under the Taylor and Francis imprint. Then there are journals such as Environment and Planning A, B, C, and D, owned by Sage. You might be uneasy to discover that if you publish under the umbrella of the former – which includes those book titles held by Routledge – then the acquisition hungry profit-making venture is listed under the FTSE 100 and has interests in pharmaceuticals, biotech and the beauty sector. Sage Publications, in contrast, will be owned by a charitable trust once its current majority owner Sara Miller, who co-founded the company in 1965, passes away. The aim being to maintain its independence in support of its credo to improve society and support the citizens of the future. It’s an interesting exercise to peruse both websites to check out the different messages and policy frameworks being communicated.

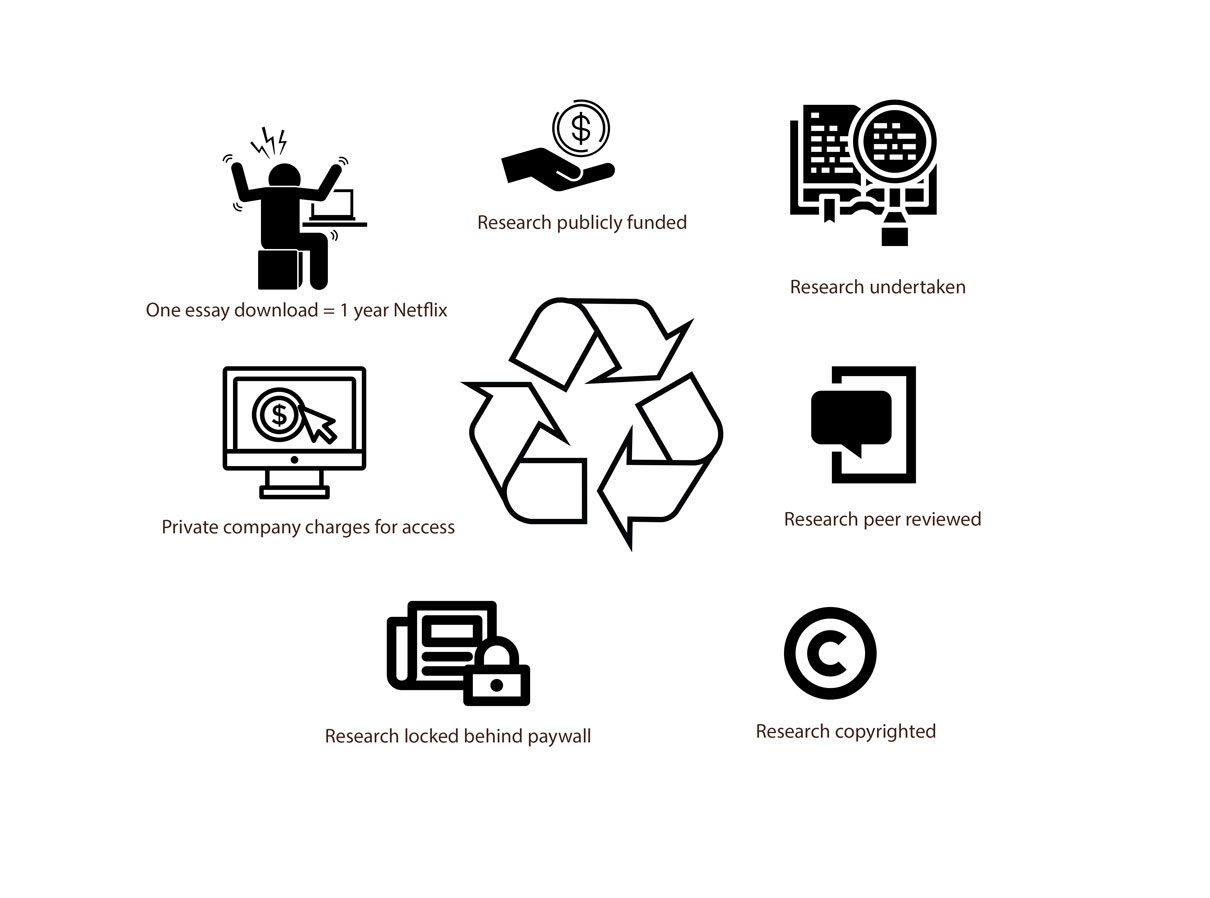

The difference and the role that profit plays is worth reflecting upon, and it’s also worth reflecting on the intellectual labour-time dedicated to producing content that is often supported by taxpayers’ money. For instance, where research is emerging from an Australian Research Council grant, or in the Swedish context where I have been working the last eight years in higher education, where your position as a civil servant means you are funded by the taxpayer toward whom you might consider yourself ethically responsible. Let’s say you want to make your publicly funded scholarship available to the public who has funded it, and yet may not have a subscription to the university library that has paid a considerable amount to include the journal in its database. You would be obliged to pay a sum, something between $1500-3000 per article maybe more, to make your work openly available. From the position of the unaffiliated, those members of the public keen to engage and read recent scholarly research, one article can cost around $AUS 60 (I just checked one of my own from Architectural Theory Review, which was published in 2010).

With popular sites like Academia.edu where scholars can build their profiles and upload pdfs of their work to be shared with others, the lines demarcating copyright permission tend to be tested. As an article I spotted in The Scholarly Kitchen points out, much of the content hosted by Academia.edu is probably illegal in terms of contravening copyright agreements, though it is complicated. Academia.edu is crafty in its insidious inflation of an anxious academic’s ego, sending notifications to alert you to how many reads you have succeeded in attracting this month, including graphs describing the analytics.

There is a catch though, should you want to know who exactly is reading you or should you want more information, then it quickly becomes a user pays system. ResearchGate, another site for building profile and rendering visible one’s research publication track record, explains that you can upload an article for private use and to be shared with co-authors. Though by rendering the name and bibliographical details of the article available, and perhaps even providing a brief abstract, eager punters may approach you to send them a copy. It remains unclear whether these and other such platforms are in any way the answer. It’s always important to ask: who is likely to profit the most? It’s unlikely to be either the academic or the curious member of the public.

In this wordy mix of profit and the well-known mantra ‘publish or perish’, you might begin to wonder where and whether words are being enunciated with a public in mind, and whatever happened to the public intellectual, and is it even possible to speak of such a thing as the public good, without being laughed at? McKenzie Wark, for her part, argues that rather than lamenting the demise of the public intellectual – here you are to think of such existentialists as de Beauvoir and Sartre – a shift in vocabulary would be worthwhile toward a thinking with general intellects, in the plural. This is a notion she gleans from Marx, nodding to the fact that today the process of extracting value from intellectual labourers has become more refined in the university sector which, as we all know, is meanwhile run like a business. General intellects make the collective attempt, despite all the considerable constraints and inevitable co-options, to offer an account of the situation we find ourselves in today as we grapple alongside so many others with the ‘forward momentum of commodification’ and its associated ‘destruction of both nature and social life.’ (McKenzie Wark, (2017) General Intellects: Twenty-One Thinkers for the Twenty-First Century, London: Verso: 3) Platforms which claim to collectivise our efforts and then sneak in a pay wall so that authors might receive more data analytics simply do not perform the task of collecting and making publicly available our shared-knowledge resources.

We might further ask who we are speaking to when we write, who is our audience and if we are reaching out far enough? If it turns out we are only speaking to ourselves and doing so in shibboleths that turn in hermeneutic circles, then no doubt it’s time to stand back and rethink our approach.

You might well be at a loss for words, but as a well-paid intellectual labourer in the university sector, it seems to me there is an urgent need for words to be spoken. At the same time – suffering and enjoying the current experience of a great slowing down brought on by the pandemic – wondering where and when words might be spoken more slowly and published at decelerated speeds?

What if you were to publish less and let the words come to you more slowly, spending some time thinking before you rush to fill the vacuum with speech? To give pause, to hesitate, amid a loss of words. I speak to myself as much to you, dear reader. For we must also remember the dearth of time available to sit down and slowly, closely, read these proliferating, sometimes profiteering, sometimes politically urgent, words.

Hélène Frichot, architectural theorist and philosopher, writer and critic, is Professor of Architecture and Philosophy, and Director of the Bachelor of Design, Faculty of Architecture, Building and Planning at the University of Melbourne. She is guest Professor, and the former Director of Critical Studies in Architecture, School of Architecture, KTH Stockholm, Sweden.