The importance of Gender Impact Assessments in shaping future cities

Words by Ella Gauci-Seddon

The Royal Commission into Family Violence and resultant legislation has brought about changes to the way that built environment professionals are required to approach design. The legislation provides frameworks to help ensure we are addressing important issues regarding gender inclusivity. Understanding and addressing gendered outcomes is now a mandatory responsibility.

In 2015, Victoria conducted Australia’s first Royal Commission on Family Violence.1 The findings revealed that to tackle family and gender-based violence, Victoria needed to address the root problem of gender inequality. The commission made 227 recommendations, one of which led to the introduction of the Victorian Gender Equality Act in 2020. This Act and its requirements have generated increased energy and efforts around the design and delivery of gender equitable cities, places and spaces.

Spatial injustice — Understanding the problem in the context of the built environment

Discussions around the gendered nature of our cities’ design and planning have been increasingly prevalent. The historical and current over representation of men in design, planning and decision making is well documented2 and significant work and research has been done to articulate the impacts that this inequity has had on our cities. These impacts range from public furniture that is designed for an average man’s body to the planning of our public transport networks. As a result, our cities are currently not equally safe, inclusive, and accessible for people of all genders and identities. And the result of this? The people who the city is not designed for are unable to participate in the world in the same way. This creates barriers to participation and contributes to broader unequal outcomes.

Understanding the Victorian Gender Equality Act

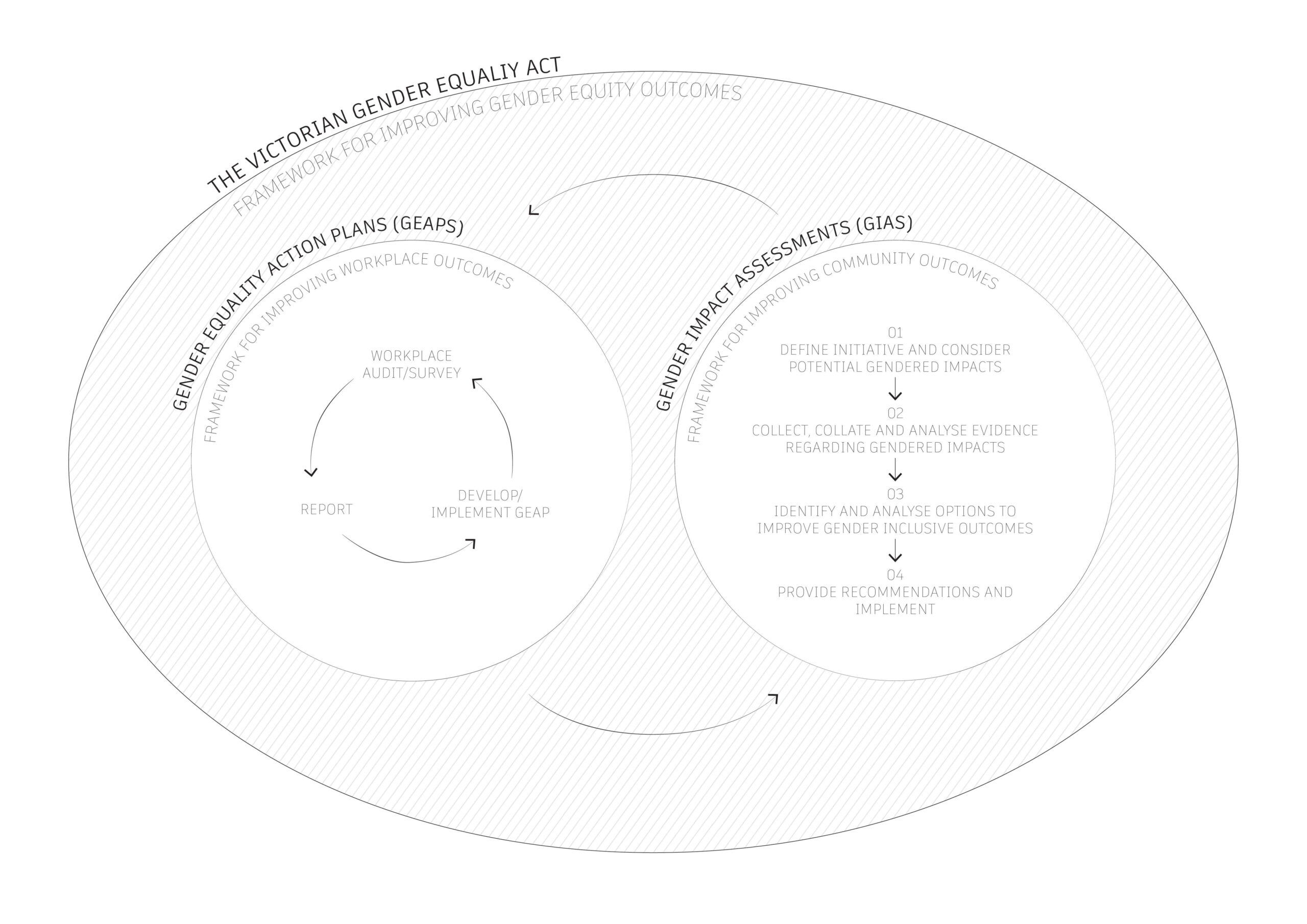

The Victorian Gender Equality Act, enacted in 2020, is a pioneering legislation that aims to advance intersectional3 gender equity by helping to identify and remove the systemic causes of gender inequality both in the workplace and in community initiatives. To achieve this, the Act requires all defined entities (primarily public sector organisations and universities) to undertake the following.

01 Take positive action in working towards gender equality within the workplace

Organisations are required to develop a Gender Equality Action Plan (GEAP). These plans must describe the status and experience of gender equality in the workplace, and detail steps to eliminate barriers and biases and increase equality for people of all genders. GEAPs are informed by data from workplace audits. In a built environment context, this step has the potential to address impacts of the over representation of men in design, planning and decision making.

02 Consider and promote gender equality in policies, programs, and services

Organisations are required to apply a gender lens to all new or updated initiatives, including the design and delivery of built environment projects. This is being done through Gender Impact Assessments, discussed further below.

This two-pronged approach ensures that the impact of the Act is broad reaching. It also acknowledges that workplaces upholding social justice principles are better equipped to deliver outcomes that advance equality, and offers the means to progress toward this objective.

Applying a gender lens through Gender Impact Assessments

While all aspects of the Act will impact how our cities are made, built environment professionals will work most directly with Gender Impact Assessments (GIAs).

What are Gender Impact Assessments?

GIAs are systematic analysis tools that are used to recognise and understand potential gendered impacts of actions or initiatives and identify positive opportunities to overcome them. They have been globally adopted and are gaining recognition as an effective means of delivering gender transformative outcomes. Under the Act GIAs must be informed by data and research. This is helping to elevate the voices of the community in the design and delivery of initiatives.

The process

Undertaking a GIA involves first defining the initiative and considering if people of different genders and intersecting identities have equal opportunity to access and use the initiative. Following this initial assessment, evidence (qualitative and quantitative data and other research) is collected, collated and analysed to further understand the potential gendered impacts of the initiative. This information is used to develop options and recommendations to mitigate these impacts and create an initiative that is inclusive and accessible for people of all genders and identities. Post occupancy assessments, evaluation and monitoring are not currently part of the GIA process, however they will be important to understand how GIAs are impacting our projects.

Why are they important?

GIAs provide organisations with a structured approach for informed decision-making. They help reduce conscious and unconscious biases by requiring evidence-based recommendations, improving gender outcomes. GIAs also influence community engagement, city planning and decision making, ensuring a broader perspective that caters to diverse community needs.

The legislation of GIAs has elevated the importance of considering and mitigating gendered impacts, providing organisations with a remit to prioritise, resource and fund this work.

Challenges

The implementation of GIAs is in its early stages and there is a lot still to be figured out. The GIA template from the Victorian Government is necessarily very general, so each organisation and department must find the right approach. Establishing ways to embed the GIA process into the design process will be important to ensure it does not create additional work, but rather strengthens existing approaches. Nevertheless, there is a strong drive to work through these challenges, and we are witnessing a shift in discussions, perspectives, and interest in the topic.

Applications within the private sector

GIAs hold significant implications for the private sector. Although not currently obligated to follow the Act, they are already encountering requirements when working with government clients. These will continue to expand.

There is an opportunity for the professional peak bodies (AILA, AIA, PIA and others) to provide forums for building and sharing knowledge around the topic in partnership with experts.

Conclusion

The Gender Equality Act has established a valuable framework for the creation of gender-inclusive cities. The effectiveness of this framework will largely depend on the way we, as professionals in the built environment, put it into practice. The legislation of GIAs elevates and ephasises the importance of gender-inclusive design, however the key to success will be moving beyond compliance. If we harness and embed this powerful tool it holds the potential to enable the delivery of gender-transformative outcomes, develop better practitioners and create better cities. Ultimately, we have an opportunity to actively contribute to the primary prevention of violence against women, children, and other marginalised communities.

Notes

1 https://www.vic.gov.au/about-royal-commission-family-violence

2 Handbook for Gender-Inclusive Urban Planning Design – The World Bank

3 Intersectionality refers to the compounding effects of discrimination that occur when someone experiences multiple marginalised identities. This creates interdependent systems of discrimination and privilege for either an individual or a group. These identities include (but are not limited to) Aboriginality, ethnicity, age, religion, race, class, sexual orientation and disability. The term was coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989.

The Gender Equality Act 2020 is the first legislation globally to require the application of an intersectional lens. This means going beyond gender and considering equity for all identities, making the impact more comprehensive.

Ella Gauci-Seddon is a senior landscape architect and gender equity lead at the City of Melbourne with experience spanning public and private sectors, academia, and the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects (AILA). Her dedication to advocacy, empowering women, and advancing young professionals in landscape architecture earned her the AILA President’s award in 2021. Ella’s passion lies in promoting equity and social justice through city and place design.